In the 1990s, we saw the rise of the memoir. “Couldn’t you add a couple of paragraphs about how memoirs glut the market?” an editor asked.

“But what’s the evidence?” There may have been evidence, but I hadn’t found it. Nobody had any numbers. They just had feelings that memoirists were whiners. If I had to say the market was glutted on the basis of a few people’s feelings, it would have been a deal-breaker for me. Quite a few memoirists write about marginalized lives, which may be why so many were eager to shut them down. Fortunately this kind editor let me be the literal-minded nerd I was.

In the twenty-first century, there are still plenty of memoirs, but we have also seen a rise in popularity of the bibliomemoir, a word I’m quite sure I didn’t invent but which isn’t in the dictionary. Some memoirs about reading are classics; others are quite pedestrian little books; but I look at all of them, because I like to know what people are reading. And since I enjoy these books, here are links to posts I’ve written about two of my favorites: Robert Dessaix’s Twilight of Love: Travels with Turgenev and Ann Hood’s Morningstar: Growing up with Books.

But there are more, more, and more being published all the time. Here are four new bibliomemoirs, three recently published and one to be published in January. I have divided them into two categories, “Intellectual” and “Common Readers.”

INTELLECTUAL BOOK MEMOIRS

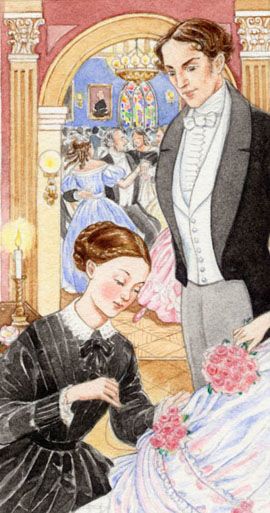

1 Elizabeth Gaskell fans will want to run to the bookstore to find their copy of Nell Stevens’ new book, The Victorian and the Romantic: A Memoir, a Love Story, and a Friendship Across Time. Why? it will complete your Gaskell mania. Hannah Rosefield has published a fascinating essay in The New Yorker about Stevens’ book and her own thoughts on Gaskell, “The Unjustly Overlooked Victorian Novelist Elizabeth Gaskell.” I do recommend it.

1 Elizabeth Gaskell fans will want to run to the bookstore to find their copy of Nell Stevens’ new book, The Victorian and the Romantic: A Memoir, a Love Story, and a Friendship Across Time. Why? it will complete your Gaskell mania. Hannah Rosefield has published a fascinating essay in The New Yorker about Stevens’ book and her own thoughts on Gaskell, “The Unjustly Overlooked Victorian Novelist Elizabeth Gaskell.” I do recommend it.

Here is the first paragraph of Rosefield’s review:

“I have always imagined [Gaskell] as somehow asexual,” Nell Stevens admits at the beginning of “The Victorian and the Romantic,” a hybrid of memoir and fictional biography that invites us to update our view of the writer. Around a third of “The Victorian and the Romantic” is a novelistic portrayal, in the second person, of Gaskell in Rome, falling in love with Norton (“You never felt lost for words, and yet for a second, now, you truly were. Your heart was beating quickly, disturbed”) and her subsequent frustrated years in Manchester, longing to see him again. The other two thirds of the book describe Stevens’s own tortured long-distance love affair with a handsome, literary Bostonian (Stevens is British), her lifelong relationship with Elizabeth Gaskell and the two-steps-forward, one-step-back progress of her Ph.D. dissertation on the transatlantic literary community in mid-nineteenth-century Rome. Along the way, Stevens volunteers for several medical trials, wins a honeymoon to India (she is single at the time), and spends several months living in a Texas tree house.

And so I have my copy of The Victorian and the Romantic and am ready to begin.

2. All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf by Katharine Smyth will be published in January, 2019. I look forward to an intriguing book about the multi-talented, charming, vulnerable, and sometimes infuriating Woolf and Smyth’s interpretation of her best book, To the Lighthouse.

2. All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf by Katharine Smyth will be published in January, 2019. I look forward to an intriguing book about the multi-talented, charming, vulnerable, and sometimes infuriating Woolf and Smyth’s interpretation of her best book, To the Lighthouse.

Here is the jacket copy:

Katharine Smyth was a student at Oxford when she first read Virginia Woolf’s modernist masterpiece To the Lighthouse in the comfort of an English sitting room, and in the companionable silence she shared with her father. After his death—a calamity that claimed her favorite person—she returned to that beloved novel as a way of wrestling with his memory and understanding her own grief.

Smyth’s story moves between the New England of her childhood and Woolf’s Cornish shores and Bloomsbury squares, exploring universal questions about family, loss, and homecoming. Through her inventive, highly personal reading of To the Lighthouse, and her artful adaptation of its groundbreaking structure, Smyth guides us toward a new vision of Woolf’s most demanding and rewarding novel—and crafts an elegant reminder of literature’s ability to clarify and console.

Braiding memoir, literary criticism, and biography, All the Lives We Ever Lived is a wholly original debut: a love letter from a daughter to her father, and from a reader to her most cherished author

COMMON READERS’ MEMOIRS

1 I know little about Sarah Clarkson’s new book, Book Girl: A Journey through the Treasures and Transforming Power of a Reading Life, but I do like the cover and the concept. It seems to be part reading memoir, part self-help book, complete with annotated book lists and a section on “what you can do to cultivate a love of reading in the growing readers around you.”

1 I know little about Sarah Clarkson’s new book, Book Girl: A Journey through the Treasures and Transforming Power of a Reading Life, but I do like the cover and the concept. It seems to be part reading memoir, part self-help book, complete with annotated book lists and a section on “what you can do to cultivate a love of reading in the growing readers around you.”

From the jacket copy:

Books were always Sarah Clarkson’s delight. Raised in the company of the lively Anne of Green Gables, the brave Pevensie children of Narnia, and the wise Austen heroines, she discovered reading early on as a daily gift, a way of encountering the world in all its wonder. But what she came to realize as an adult was just how powerfully books had shaped her as a woman to live a story within that world, to be a lifelong learner, to grasp hope in struggle, and to create and act with courage.

2. Then there’s I’d Rather Be Reading: The Delights and Dilemmas of the Reading Life by Anne Bogel, a lifestyle and book blogger at the site Modern Mrs. Darcy.

2. Then there’s I’d Rather Be Reading: The Delights and Dilemmas of the Reading Life by Anne Bogel, a lifestyle and book blogger at the site Modern Mrs. Darcy.

Here’s the jacket copy:

For so many people, reading isn’t just a hobby or a way to pass the time–it’s a lifestyle. Our books shape us, define us, enchant us, and even sometimes infuriate us. Our books are a part of who we are as people, and we can’t imagine life without them.

I’d Rather Be Reading is the perfect literary companion for everyone who feels that way. In this collection of charming and relatable reflections on the reading life, beloved blogger and author Anne Bogel leads readers to remember the book that first hooked them, the place where they first fell in love with reading, and all of the moments afterward that helped make them the reader they are today. Known as a reading tastemaker through her popular podcast What Should I Read Next?, Bogel invites book lovers into a community of like-minded people to discover new ways to approach literature, learn fascinating new things about books and publishing, and reflect on the role reading plays in their lives.

I read the sample and it is quite well-written. It’s on my TBR list.

What bibliomemoirs do you admire and do you know of any new ones?