When it’s dark on the dot of five in winter, I need more than a Diet Coke to perk up.

All those hours and hours of winter darkness…

Maybe a few cookies and a Victorian novel

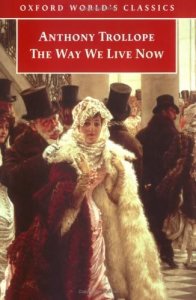

I recently reread Trollope’s The Way We Live Now, a stunning novel about financial fraud, desperate aristocrats, calculated courtships, and literary corruption.

According to John Sutherland in the introduction to The Way We Live Now (Oxford World Classics, 1982), Trollope wrote this superb satire in reaction to the dishonesty and corruption he observed in London when he returned after a year and a half in “the colonies.” The book is witty and absorbing, but is not for the faint of heart: it is the longest of his works, at 425,000 words.

A financial scam is at the heart of this novel, and I was faintly reminded of the financial collapse in 2008. Finance is not always based on real money (and that’s as far as my financial knowledge goes). Trollope’s book revolves around Melmotte, a wealthy financier of mysterious origins who suddenly moves to London with his family. He directs the board of the South Central Pacific and Mexican Railway, and whether or not the railroad actually exists, shares are briskly bought and sold.

A financial scam is at the heart of this novel, and I was faintly reminded of the financial collapse in 2008. Finance is not always based on real money (and that’s as far as my financial knowledge goes). Trollope’s book revolves around Melmotte, a wealthy financier of mysterious origins who suddenly moves to London with his family. He directs the board of the South Central Pacific and Mexican Railway, and whether or not the railroad actually exists, shares are briskly bought and sold.

Who is Melmotte? Nobody knows. It is doubted that he is English. His manners are atrocious, and his arrogance is enthralling. He throws tantrums over a dinner he is to give for the Chinese emperor, and wins an election as a Conservative candidate for Parliament, even though he gives money both to the Catholic church and the Protestants. Oddly, he becomes more sympathetic as the book goes on, and, in a way, he reminds me of Soames in The Forsyte Saga.

None of Trollope’s characters respect Melmotte: they want to use him. Most of them move in higher social circles. Roger Carbury, the squire of Carbury Hall, says that Melmotte is “a sign of degeneracy.” “What are we coming to when such as he is an honoured guest at our tables?”

As usual, Trollope’s women are fascinating. I very much enjoyed reading about Lady Carbury, a widow who has turned to writing because her handsome, evil son, Sir Felix, has run through all his money. Her literary exploits are both hilarious and sad: she manages to get a few good reviews for her short book, Criminal Queens, because of her connections with editors. Trollope’s descriptions of her ceaseless networking seem very realistic.

But she can’t control all the reviewers, and is devastated that “one of Alf’s most sharp-nailed subordinates had been set upon her book, and had pulled it to pieces with rabid malignity.”

Trollope writes,

Of all reviews, the crushing review is the most popular, as being the most readable. When the rumour goes abroad that some notable man has been actually crushed, been positively driven over by an entire juggernaut’s car of criticism till his literary body be a mere amorphous mass, then a real success has been achieved, and the Alf of the day has done a great thing.

Lady Carbury also schemes for both her children to marry money: she urges Sir Felix to marry Melmotte’s daughter, Marie, and insists that her daughter, Hetta, must marry her reliable cousin Roger Carbury, who also has money. Lady Carbury has bad values, but she is desperate, especially on behalf of her beloved, if sociopathic, son. Unfortunately for Roger, who adores Hetta, she is in love with his friend, Paul Montague, a very attractive but weak character.

The women in The Way We Live Now are reluctant to marry the men chosen for them. Lady Harbury hesitates to marry a besotted editor; Melmotte’s daughter, Marie, plans to run away with Felix instead of marry the man to whom her father betroths her; Ruby Ruggles runs away from marriage to a country bumpkin to London to be near Sir Felix, who has been flirting with her; and Georgiana Longstaffe is on the shelf so long she longs to marry a rich middle-aged Jewish merchant she meets at Melmottes’s house (and, yes, her parents are anti-Semitic, and Trollope’s views on Jews are also dicey).

But my favorite character is Mrs. Hurtle, an American widow who travels to London to claim Paul Montague, her fiance, after he writes to break off the proposal. She is witty, charming, smart, and has money, and though her reputation is bad–she has shot a man in Oregon and her husband might not actually be dead–she has traveled with and lived with Paul, and one cannot help but think he is a fool to prefer Hetta to Mrs. Hurtle. (But Mrs. Hurtle knows she has no chance against the virgin, Hetta.)

You can read Trollope’s novel on many levels. It is a novel about money, and it is a novel about marriage.

And much more.

These are just a few notes.

So much fun to read. I always love Trollope.

It sounds wonderful – and I have a copy! Now I just need the time…. (Odd you should say what you do about Soames – despite his awful behaviour, I find him myself feeling sorry for him in a Karenin-type of way!)

LikeLike

It is very entertaining. I must admit that Melmotte IS very bad–Soames would never commit fraud–but Melmotte holds his head up and tries to behave well once his prestige is gone.

LikeLike

I’m with you in having thoroughly enjoyed The Way We Live Now. It is a rich treat with so many important themes related to literature and money. If you enjoyed Lady Carbury, you would probably enjoy Frances Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans. She was Anthony Trollope’s mother and supposedly Lady Carbury is based on her. If so, she could do worse. Frances Trollope was brave, observant and able to keep the reader’s attention.

I am re-watching the old Forsyte TV series and, yes, Soames becomes more sympathetic. Partly it is because he genuinely loves Fleur, his daughter, probably because he sees her as an extension of himself (his property). It is also because as the period gets into the 1920s, Soames’ honesty is in contrast to some less attractive characters.

LikeLike

Nancy, I have read Frances Trollope’s “Domestic Manners of the Americans. Lots of Americans spitting in dining rooms on steamboats, as I remember! ” I wonder what her other books are like. It doesn’t surprise me that Lady Carbury is based on her. Trollope really knew his literary life!

I really love the old Forsyte series. It was so well-done. There is also a BBC “The Way We Live Now,” which I keep forgetting to get at the library.

LikeLike

David Suchet as Melmotte in the BBC TWWLN was amazing. He dominated every scene he appeared in.

LikeLike

David Suchet would be perfect. I must see that.

LikeLike

The BBC series is one of the best things they’ve done. Melmotte is both despicable and sympathetic. I did read a Frances Trollope novel, The Widow Barnaby, and found it enjoyable. Anthony must have gotten his sense of humor from his mother because the Widow Barnaby is quite a lot of fun (unintentional on the widow’s part).

LikeLike

Nancy, I must see the series!

I see that Project Gutenberg has Frances’ The Widow Barnaby. Maybe one of these days I’ll get to it. This is one of those times when e-readers are really fun.:)

LikeLike

While in Trollope’s book, Mrs Hurtle is very much a tertiary character by the novel’s end she is the most poignant of the women characters. She was emphasized in the recent film adaptation where the actress was beautiful but not poignant. She in John Wirenius’s sequel, Phineas at Bay, as Winifred Vavasour who married George Vavasour ….

LikeLike

Mrs. Hurtle was fascinating. I do want to see the film adaptation. I had no idea there was a sequel by John Wirenius.

LikeLike

Pingback: When Everything We Read Applies: Trollope’s The Way We Live Now and Cicero’s Pro Archia – mirabile dictu