There has not been enough rock and roll here lately.

There has not been enough rock and roll here lately.

My mother was not bookish, but she encouraged bookishness.

She read to me day and night until I learned to read. I bounced into her room at 5 a.m. to beg her to read She read nursery rhymes (I was partial to Three Little Kittens), fairy tales, and Make Way for Ducklings.

How glad she must have been when I learned to read!

I owe my bookishness to Mom, whom I miss very much, so I am dedicating this List of Favorite Books of the Decades of My Life to her. I am listing only one per decade, so it is a bit arbitrary. Lists are fun!

My first decade (zero to nine): E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle. This is a classic, my favorite of Nesbit’s fantasies. It is the story of the “magic adventures” of Gerald, Jimmy, and Kathleen (siblings), and a friend, Mabel. The three siblings wander into the garden of a castle and see Mabel dressed up like a princess and feigning an enchanted sleep. When she is kissed, she convinces them she is a princess and says she has a magic ring–and then, to her consternation, it becomes true. She wishes she were invisible–and becomes invisible. She doesn’t believe they can’t see her–and shakes them. The sight of their being shaken by someone invisible is terrifying. They clutch her invisible arms and legs. In each chapter, they have a different adventure with the ring. I especially remember a frightening chapter when the statues come to life.

My first decade (zero to nine): E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle. This is a classic, my favorite of Nesbit’s fantasies. It is the story of the “magic adventures” of Gerald, Jimmy, and Kathleen (siblings), and a friend, Mabel. The three siblings wander into the garden of a castle and see Mabel dressed up like a princess and feigning an enchanted sleep. When she is kissed, she convinces them she is a princess and says she has a magic ring–and then, to her consternation, it becomes true. She wishes she were invisible–and becomes invisible. She doesn’t believe they can’t see her–and shakes them. The sight of their being shaken by someone invisible is terrifying. They clutch her invisible arms and legs. In each chapter, they have a different adventure with the ring. I especially remember a frightening chapter when the statues come to life.

My second decade (ten to nineteen): Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. The Nobel Prize winner’s powerful experimental novel centers on Anna, a writer and single mother whose life is fragmented because she no longer respects her fiction-writing. She has contempt for her best-selling novel about an interracial relationship in Africa, is a disillusioned leftist who once idealized the Soviet Union,,and can only fall in love with men who cannot love deeply. Lessing also chronicles a collapsed society, broken by the trauma of World War II, fear of the bomb, and emotional frigidity.

My second decade (ten to nineteen): Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. The Nobel Prize winner’s powerful experimental novel centers on Anna, a writer and single mother whose life is fragmented because she no longer respects her fiction-writing. She has contempt for her best-selling novel about an interracial relationship in Africa, is a disillusioned leftist who once idealized the Soviet Union,,and can only fall in love with men who cannot love deeply. Lessing also chronicles a collapsed society, broken by the trauma of World War II, fear of the bomb, and emotional frigidity.

The experimental structure of the novel is bold. Lessing alternates sections of a short traditional novel about Anna, “Free Women,” with Anna’s writings in four notebooks–black, red, yellow, and blue–in which she tries to measure out the truth about her life of organized chaos, often writing in fragments, experimenting with different styles, chronicling her experience straightforwardly in the communist party in Africa, her marriage and love affairs, her difficulty with writing. She also writes a novel about an alter ego, Ella, who is more brittle than Anna, but undergoes similar emotional upheaval. Eventually she receives a golden notebook…

My third decade (twenty to twenty-nine): Margaret Drabble’s The Realms of Gold. At the beginning of this fascinating, insightful, analytical, but ultimately cheerful book, Frances Wingate, a brilliant archaeologist, is in her hotel room suffering from depression. The next day she must give a lecture, and, having idly visited the city’s octopus research laboratory, she is thinking about the octopus who lived in a plastic box with holes for its arms. The female octopus is programmed to die after giving birth: what has Frances been programmed for? She wonders. What are middle-aged women supposed to do when they no longer have babies? Her children are fine. She has her work.

My third decade (twenty to twenty-nine): Margaret Drabble’s The Realms of Gold. At the beginning of this fascinating, insightful, analytical, but ultimately cheerful book, Frances Wingate, a brilliant archaeologist, is in her hotel room suffering from depression. The next day she must give a lecture, and, having idly visited the city’s octopus research laboratory, she is thinking about the octopus who lived in a plastic box with holes for its arms. The female octopus is programmed to die after giving birth: what has Frances been programmed for? She wonders. What are middle-aged women supposed to do when they no longer have babies? Her children are fine. She has her work.

Frances has some non-biological reasons to be depressed. She broke up with her lover, Karel, a professor, adult education teacher, and misses him badly. She even carries a bridge of two of Karel’s false teeth, sometimes in her bosom to “protect her virtue.” He was married, and she was suddenly disturbed by the fact they had only managed to get away for four days away in the years of their relationship. She told him she didn’t want to see him anymore.

Thee novel is also a dark exploration of family, heredity, and “the landscape of the soul.” Frances is fascinated by herroots, and we learn about her relative Janet Bird, a trapped housewife in Tockley, France’s hometown. . There is something profoundly optimistic about Frances, the second generation away from Tockley. And that is why we like this book so much.

My fourth decade (thirty to thirty-nine): Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. The plot of OMF revolves around money: the effect of the inheritance of the riches of a miserly junkyard owner on his heirs, the Boffins who worked as his servants; they believe his son, John Harmon has been murdered. Members of the Boffins’ circle include John Rokeman, the mysterious secretary who dedicates himself passionately to their interests; the beautiful, greedy, witty Bella, whom the Boffins informally adopt; poisonous Wegg, the one-legged con man who hopes to blackmail Mr. Boffin; and Betty Higden, the independent old woman who refuses to accept money from the Boffins because she wants to stand on her own two feet and, by her own money, keep out of the workhouse.

My fourth decade (thirty to thirty-nine): Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. The plot of OMF revolves around money: the effect of the inheritance of the riches of a miserly junkyard owner on his heirs, the Boffins who worked as his servants; they believe his son, John Harmon has been murdered. Members of the Boffins’ circle include John Rokeman, the mysterious secretary who dedicates himself passionately to their interests; the beautiful, greedy, witty Bella, whom the Boffins informally adopt; poisonous Wegg, the one-legged con man who hopes to blackmail Mr. Boffin; and Betty Higden, the independent old woman who refuses to accept money from the Boffins because she wants to stand on her own two feet and, by her own money, keep out of the workhouse.

There are also sub-Boffin circles: Lizzie Hexam and her father, Gaffer Hexam, a waterman, find the body of John Harmon in the Thames. Mortimer Lightwood, the Boffins’ lawyer, and his good friend and fellow lawyer, the witty, languorous Eugene Wrayburn, meet them when they come to identify the body. And thus they are all connected to the Boffins.

And there is a shallow monied sub-culture which is hilarious: the Veneerings, social climbers, invite everybody and anybody who seems to have money to dinner as part of their scheme to claw their way to the top of the precarious ladder of high society. Lightwood and Wrayburn are members of this group, though they seem not to know why they are there or want to be there. And Dickens’ portrayal of this group is an education in what kind of person not to aspire to know. In this whole layer of society, as we learn as the book progresses, there are only a few good souls.

My fifth decade (forty to forty-nine): Charlotte Bronte’s Villette. To a woman of a certain age, Bronte’s Villette, an unflinching report of solitude and isolation, is more interesting than Jane Eyre. This bold novel is tougher and yet more nuanced than Jane Eyre, and feminist readers and Bronte fans should give it another chance.

My fifth decade (forty to forty-nine): Charlotte Bronte’s Villette. To a woman of a certain age, Bronte’s Villette, an unflinching report of solitude and isolation, is more interesting than Jane Eyre. This bold novel is tougher and yet more nuanced than Jane Eyre, and feminist readers and Bronte fans should give it another chance.

Lucy Snowe, the solitary narrator, is the invisible woman in triangular relationships. Attachments become triangulated without her realizing it whenever she has a relationship with a man.

When we first meet Lucy, she seems cold. There is something voyeuristic about Lucy’s cold scrutiny of her godmother Mrs. Bretton’, though she loves her godmother. As a teenage girl, Lucy has no interest in Graham Bretton, the handsome, lively teenage son. But in minute detail Lucy describes Graham’s friendship with Polly, a small child who becomes passionately fond of Graham when she stays with the Brettons during her father’s illness. Graham teases her and behaves like an older brother, while Polly is like a tiny woman. Lucy cannot understand the magnitude of the child’s attachment.

Lucy is shadowy. She tells us very little about her family, and there is a Gothic mystery about her intense solitude and taciturnity.

Then as an adult she is thrown on the world without money, and eventually ends up a teacher at Madame Beck’s school in Villette (an imaginary city like Brussels, where Bronte taught) and meets Graham Bretton (now called Dr. John) again.

And you can read the rest of this “review” here.

YOU’LL HAVE TO WAIT TILL I FINISH MY SIXTH DECADE FOR MORE. 🙂

I sat in bed reading the new Folio Society edition of Trollope’s The Duke’s Children.

It is as big as a dictionary. Maybe a Complete Shakespeare.

It is a beautiful book. It duplicates the design of Ye Olde Book, with a leather binding and gilded edges.

The Folio Society’s new complete four-volume edition of The Duke’s Children (it was originally published as a three-volume book and the missing volume has been restored) has gotten good press: John McCourt at The Irish Times loved it. He wrote:

Standard editions of The Duke’s Children still read well and hold their ground against other works in the Palliser series, but the reborn text is of a much richer fabric. Shorn of its short cuts, and with all its details of plot, character, setting and narrative tone restored, it functions far more effectively both as a stand-alone novel and as the last of a long series full of familiar names, characters, settings and themes.

Alas, it is too unwieldy to read in the supine position.

I know, I know. I should sit up.

I am going back to my Oxford paperback. I can’t read oversized books at my age.

What to do with my Folio Society edition? Sponsor a contest at Mirabile Dictu? Make everybody write an essay about why they deserve the book?

That would be crazy, wouldn’t it?

And so I donated it to the Planned Parenthood Book Sale. I stuck it in a bag and put it in my bike pannier. Then I had to find the Planned Parenthood book drop.

I got lost in the inner city on my bike. I was sure the map had said to head north. Sure, it was north–north of a street a few blocks south!

I finally found it and dropped off the book. After a decade of shopping at the Planned Parenthood Book Sale, I am happy to give them a valuable book. I hope they make a huge profit.

I love the Folio Society’s clothbound books, and own one of the Thomas Hardy books. They are normal-sized books: a little tall, but readable in bed.

But I regard The Duke’s Children as a mirabile dictu folly! What was I thinking?

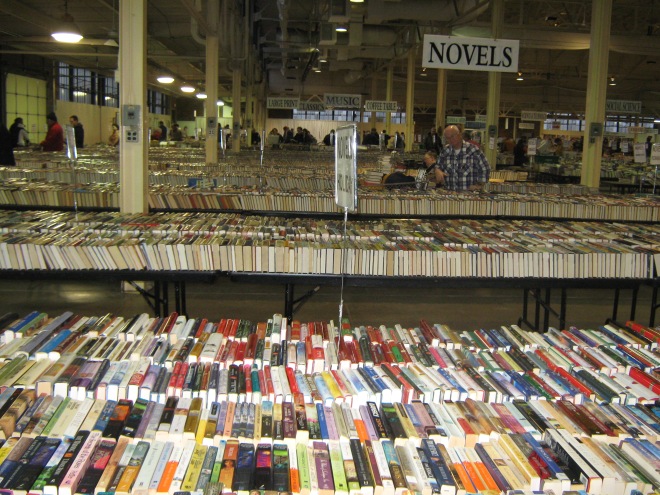

The Planned Parenthood Book Sale is a perk of Midwestern living. It is held on the Iowa State Fairgrounds in Des Moines April 16 (today) through April 20..

The Planned Parenthood Book Sale is a perk of Midwestern living. It is held on the Iowa State Fairgrounds in Des Moines April 16 (today) through April 20..

Scruffy bibliophiles and book scouts lined up eagerly, as though attending the premiere of a Star Wars movie. When the doors opened at 3, they made a mad dash inside. Well, semi-mad: this is Des Moines. They stopped at the door to pay the $10 entry fee.

Scruffy bibliophiles and book scouts lined up eagerly, as though attending the premiere of a Star Wars movie. When the doors opened at 3, they made a mad dash inside. Well, semi-mad: this is Des Moines. They stopped at the door to pay the $10 entry fee.

I found some gems, even first editions. The prices are dirt-cheap: mine ranged from 50 cents to $4.50. I look for reading-in-bed copies in good shape. I found a lot of wonderful books.

I came home with a box-full Here they are!

A hardcover copy of Daphne du Maurier’s The Doll: The Lost Short Stories, originally published in periodicals during the 1930s. Price: $2.50.

A hardcover copy of Daphne du Maurier’s The Doll: The Lost Short Stories, originally published in periodicals during the 1930s. Price: $2.50.

A first edition of Gladys Taber’s novel, Spring Harvest. Price: $1.00. The film Christmas in Connecticut is based loosely on Taber’s columns for Family Circle and Ladies’ Home Journal. She wrote novels, nature books, cookbooks, and books about living in a Connecticut farmhouse. (I posted on two of my favorite Tabers, Country Chronicle here and Mrs. Daffodil here.)

A hardcover edition of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. $3.50.

A book club edition of The Deadly Decisions by Helen MacInnes, an omnibus containing two novels, Decision at Delphi and The Venetian Affair. $1.00

An Oxford paperback of Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. $3.00. Just think, if I like this one, he wrote dozens!)

An Oxford paperback of Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. $3.00. Just think, if I like this one, he wrote dozens!)

A Penguin of Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt. This is a replacement copy for a book that fell apart. $2.50.

A Book Club hardcover edition of Mary Stewart’s The Moon-Spinners, my favorite “Gothic novel,” as we used to call them, set in Crete, published in 1962. $1.00

A Book Club hardcover edition of Mary Stewart’s The Moon-Spinners, my favorite “Gothic novel,” as we used to call them, set in Crete, published in 1962. $1.00

A People’s Book Club edition of Mary Stolz’s Ready or Not. $1.00. The cover flap says: “Gentle, capable Megan Connor had long carried the responsiblity of making a happy home for her widowed father Fan, her sister Julie, and her brother Ned.” Then she falls in love apparently. Stolz was a writer of Y.A. ficiton. I couldn’t resist the end paper.

Rock on!

A paperback of Elizabeth Strout’s The Burgess Boys. I have long meant to read something by this Pulitzer Prize winner. $3.00

A paperback of Elizabeth Strout’s The Burgess Boys. I have long meant to read something by this Pulitzer Prize winner. $3.00

A paperback of Alice Hoffman’s Blackbird House. $3.00. I never got around to this one.

A Europa edition of Orange Prize finalist Deirdre Madden’s Time Present and Time Past. $4.00

A Europa edition of Orange Prize finalist Deirdre Madden’s Time Present and Time Past. $4.00

Orange Prize winner Lionel Shriver’s 2007 novel The Post-Birthday World. $3.00. I loved her novel Big Brother and she generously give us a Q&A interview in 2013.

The black book is Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar ($2.50) and the red is John Buchan’s The Blanket of the Dark ($1.00).

The black book is Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar ($2.50) and the red is John Buchan’s The Blanket of the Dark ($1.00).

A first edition of Louise Dickinson’s classic, We Took to the Woods, her autobiographical book about living in a cabin in the woods of Maine. $5.00. ANd I love the map on the end page.

Elizabeth Cadell’s The Waiting Game. She has been compared to D. E. Stevenson: we’ll see! $1.00

And a new unread Penguin of John O’Hara’s Ten-North Frederick, the winner of the National Book Award. $3.00

And, last , an unread paperback copy of H. V. Morton’s In Search of London. $1.00

And, last , an unread paperback copy of H. V. Morton’s In Search of London. $1.00

Do let’s hope this keeps me busy for a while. I hardly think I need to buy another book this year. Ha ha!

The Barnes & Noble bags have undergone a redesign.

The Barnes & Noble bags have undergone a redesign.

An illustration on one side depicts the Great White Whale diving into the opening paragraph of Moby Dick. (“Call me Ishmael.”) On the flip side, Huckleberry Finn sits against a tree and smokes a pipe. (“You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sayer; but that ain’t no matter.”)

The good news: they’re pretty.

The bad news: they’re plastic.

The bad news: they’re plastic.

“They’re not destroying the ozone layer,” said my go-to air pollution control engineer friend. “See that HDPE triangle? That stands for High Density Polyethylene. Yes, they are made from petroleum. That’s oil. That causes pollution. But this plastic is recyclable. And there are also issues with paper.”

The B&N bag says, PLEASE REUSE OR RECYCLE AT A PARTICIPATING STORE. I hope my local store participates.

The B&N bag says, PLEASE REUSE OR RECYCLE AT A PARTICIPATING STORE. I hope my local store participates.

Meanwhile, I must remember to say I don’t need a bag. We already have a drawer full of plastic bags to return to stores.

************************************************

THE PENNY DREADFUL SCENE ONLINE.

Okay, they’re not really penny dreadfuls.

Do you every buy used books for a penny at Amazon?

In recent months, I have paid a penny for a used hardback of Carolyn Heilbrun’s Writing a Woman’s Life and a paperback of Iris Murdoch’s The Nice and the Good. Both were in good shape. The trick is to know who is a reliable bookseller.

In recent months, I have paid a penny for a used hardback of Carolyn Heilbrun’s Writing a Woman’s Life and a paperback of Iris Murdoch’s The Nice and the Good. Both were in good shape. The trick is to know who is a reliable bookseller.

As far as my husband knows, every book I buy costs a penny. “I got a deal on that,” I say when a package arrives.

The shipping cost is $3.99, so a penny book actually costs $4. Still, that is very cheap when you’re able to track down a book you want but are not able to buy locally.

How do stores make money off penny books?

On April 14, The Guardian ran an excellent article on the subject. Calum Marsh reports that some of the huge online stores, like Thrift Books, cart away truck loads of books from Goodwill, public libraries, and charity shops. They sift through the piles and find some valuable books, sell others for a penny, and pulp the junk. They make only a few cents on penny books, but it is profitable if their volume is great.

The English bookseller Colin Stephens, founder and director of Sunrise Books, sends two vans out every day to charity shops to collect their unwanted used books. Stephens got his start in a very peculiar way. He

was thumbing through a charity shop’s bookshelf when the manager told him how much she’d come to hate used books. Every few days, she complained, she would have to load the trunk of her car with the shop’s excess donations and shuttle them to the landfill, in her own spare time and at her own expense

So that’s where penny books come from.

“Who is your favorite writer?” a Famous (Now Dead) White Male Writer asked during an interview on a book tour while I scribbled everything he said in a notebook.

“Thomas Hardy,” I said.

Hardy was my secret love.

“Hardy was our grandfathers’ writer,” he said.

I said nothing.

But I was so humiliated by his condescension that I didn’t read Hardy again until the millennium.

Good God, I think in retrospect. Why let a little embarrassment keep one from reading a great English writer?

Thomas Hardy vs. the Famous (Now Dead) White Male Writer?

Hardy is a surprisingly edgy writer.

I recently reread Hardy’s ninth novel, Two on a Tower, published in 1882.

I recently reread Hardy’s ninth novel, Two on a Tower, published in 1882.

In this lyrical, gorgeous, rather weird novel, he relates the story of the tragic love affair of a beautiful, depressed woman and a brilliant young astronomer.

Two on a Tower is a predecessor of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Both center on clandestine love affairs between a sensitive lady and an intelligent man of a lower class. The heroines have similar names: Hardy’s is Lady Viviette Constantine, and Lawrence’s is Lady Constance Chatterley.

The atmospheric first few pages of Two on a Tower not only set the scene but establish Hardy as a stunning poet.

On an early winter afternoon, clear but not cold, when the vegetable world was a weird multitude of skeletons through whose ribs the sun shone freely, a gleaming landau came to a pause on the crest of a hill in Wessex. The spot was where the old Melchester Road, which the carriage had hitherto followed, was joined by a drive that led round into a park at no great distance off.

What Gothic imagery! I especially like “the vegetable world was a weird multitude of skeletons…”

The heroine, Lady Vivette Constantine, is fascinated by the view of the tall tower on top of the hill. A few months later, when the weather is more clement, she walks across the fields and climbs to the top of the tower. There she meets Swithin St. Cleeve, a handsome young astronomer who is using the tower as an observatory. Swithin is the orphaned son of a curate-turned-farmer and a farmer’s daughter.

And thus the constant Viviette falls in love, though she constantly feels guilty. She is ten years older than he, and she is terrified of gossip.

She becomes fascinated by astronomy–she has had nothing to do–and buys equipment for his observatory. Her husband, Sir Blount, has been absent for three years on a hunting expedition in Africa. Before he left, he demanded that she “not so behave towards other men as to bring the name of Constantine into suspicion…” And when she asks the rector, Mr. Torkingham, whether she need continue to refuse social invitations and “live like a cloistered nun in his absence,” he advises her to keep her word.

She becomes fascinated by astronomy–she has had nothing to do–and buys equipment for his observatory. Her husband, Sir Blount, has been absent for three years on a hunting expedition in Africa. Before he left, he demanded that she “not so behave towards other men as to bring the name of Constantine into suspicion…” And when she asks the rector, Mr. Torkingham, whether she need continue to refuse social invitations and “live like a cloistered nun in his absence,” he advises her to keep her word.

There is much irony in the narrative. Swithin does ground-breaking research only to find that someone has just published the same results. Viviette hears rumors about Sir Blount’s whereabouts: first, that he is in London; then, that he is dead. Even after they hear that he is dead, the class-conscious Viviette and poverty-stricken Swithin marry secretly because of Viviette’s social position: she is tormented by fear of scandal over different class and age and the need to conform. On the day of the wedding, Swithin receives a letter saying that his uncle has left him 600 pounds a year on the condition that he not marry till he is twenty-five. He sacrifices the legacy for the marriage and does not tell Viviette about it. There are many ripple effects of the secret marriage. They deceive Viviette’s brother and the Bishop about their relationship. Then their marriage turns out to be invalid because the rumor of Sir Blount’s death had been false and he had died after the date of their wedding.

There is much irony in the narrative. Swithin does ground-breaking research only to find that someone has just published the same results. Viviette hears rumors about Sir Blount’s whereabouts: first, that he is in London; then, that he is dead. Even after they hear that he is dead, the class-conscious Viviette and poverty-stricken Swithin marry secretly because of Viviette’s social position: she is tormented by fear of scandal over different class and age and the need to conform. On the day of the wedding, Swithin receives a letter saying that his uncle has left him 600 pounds a year on the condition that he not marry till he is twenty-five. He sacrifices the legacy for the marriage and does not tell Viviette about it. There are many ripple effects of the secret marriage. They deceive Viviette’s brother and the Bishop about their relationship. Then their marriage turns out to be invalid because the rumor of Sir Blount’s death had been false and he had died after the date of their wedding.

When Two on a Tower was published in 1882, it disturbed critics nearly as much as Lawrence’s much more graphic Lady Chatterley’s Lover did in 1928. The biographer Carl Weber reported that reviewers described Hardy’s novel as “’hazardous,’ ‘repulsive,’ ‘little short of revolting,’ [and] ‘a studied and gratuitous insult.’”

Hardy wrote in a letter to Edmund Gosse on Dec. 10, 1882 (Purdy and Millgate 110): “I get most extraordinary criticisms of T. on a T. Eminent critics write & tell me in private that it is the most original thing I have done…while other eminent critics (I wonder if they are the same) print the most cutting rebukes you can conceive–show me (to my amazement) that I am quite an immoral person…”

Different times, different mores.

Wendy Pollard, the author of a brilliant new biography, Pamela Hansford Johnson: Her Life, Works and Times, kindly agreed to an e-mail interview.

Pamela Hansford Johnson (1912-1981), a critically-acclaimed novelist whose books are now neglected, wrote some of my favorite novels, among them the Helena trilogy, Too Dear for My Possessing, An Avenue of Stone, and A Summer to Decide. She was married to C. P. Snow, another brilliant but neglected novelist.

I raced through Wendy’s engrossing biography, which is one of my favorite books this year.

Kat: What drew you to write about Pamela Hansford Johnson, a brilliant 20th-century novelist and influential critic whose work is largely forgotten?

Wendy Pollard: I’ll have to go back quite some time to explain! I did not go to university at 18, but decided to catch up much later by taking an interdisciplinary degree with the wonderful institution we have in the UK – the Open University. I became drawn to the literature element of the various modules, and was fortunate enough later to be offered a place to study for a PhD in Cambridge. I chose 20th century literary reception for the topic of my dissertation, focusing on the novels of Rosamond Lehmann. Even at the comparatively recent date of 1996, some eyebrows were raised in the English Faculty with regard to the suitability of that choice, since Lehmann was regarded as falling into an unnamed category between highbrow and middlebrow.

In the 1920s, when what Virginia Woolf later labelled ‘the battle of the brows’ was occupying the minds of the literati, J.B. Priestley had suggested a cross-over category, ‘broadbrow’, only to receive a hostile reaction from the highbrows who held sway. This seems to me to have been a great shame, and when I was trying to decide on a writer for a biography which I hoped would appeal to appreciative non-specialist readers as well as to academics, I remembered how much I had enjoyed Pamela Hansford Johnson’s novels while I was growing up, and realised that she could be regarded as the epitome of ‘broadbrow’.

I have to admit that, at that time, I knew very little about PHJ’s poetry, plays and works of criticism, nor about her interesting life she had led and her circle of friends and acquaintances in the UK, the US and Russia, and I certainly had no idea of the biographer’s dream of an Aladdin’s Cave of source material awaiting me. This leads on to your next question.

Kat: How does a biographer shape a coherent narrative? Does the research suddenly click and fit together? What material was especially helpful?

Wendy Pollard: I had the greatest good fortune to receive the co-operation of Pamela’s daughter, Lindsay Avebury, who is her mother’s literary executor, together with her brother, Andrew, and also Philip Snow, the son of PHJ and her second husband, C.P. Snow.

Lindsay allowed me to read and transcribe the diaries her mother had kept from the age of fifteen. Pamela would have had no idea of a biographer’s future interest in them at the outset, but they provided the perfect framework. Lindsay also reminisced to me about her mother and showed me her collection of as yet unarchived letters, photographs and other family memorabilia. I was able to locate further material in literary archives both in England and in America. It can be so exciting to come across a missing piece of the jigsaw. I get huge pleasure from research, but sometimes have to discipline myself to leave out descriptions of events or anecdotes enjoyable in themselves, but not strictly relevant to the story being told.

Kat: This is a very literary biography, containing precis and critiques of her books and a history of their reception. Was it more difficult to write about her life or her books?

Wendy Pollard: I enjoyed writing about the connections between the two, although PHJ did not write directly autobiographical novels on the scale of CPS. Literary theory, when I was completing my first degree, was agreeing with Roland Barthes that the author was dead, but fortunately that school of thought has given way.

I did experience some guilt about revealing some aspects of her life. In her diaries, towards the end of her life, as you will have read, she did occasionally directly admonish any would-be biographer, but I felt a responsibility not to suppress relevant facts.

I found the history of the reception of her work particularly interesting as her novels generally received excellent reviews during her lifetime, but I maintain that contemporary literary feuds have played a significant part in the posthumous and (as I’m so glad that you and I agree) unjustifiable neglect of her writings.

Kat: What is your favorite book by Johnson?

Wendy Pollard: This is a tricky question and I’m going to hedge a bit. She was so prolific, and her novels encompass several genres: the answer might depend on my mood. Too Dear for My Possessing, the first novel of her acclaimed ‘Helena’ trilogy, is very fine, combining romanticism with a compelling account of the social and political background of the 1920s and 1930s. As a girl, I loved Catherine Carter, her Dickensian novel about the Victorian stage, and I still reread this from time to time for comfort. Finally, if I wanted to tussle with one of the moral problems which feature in her later novels, I would choose The Humbler Creation, which, despite its central dilemma, does also illustrate PHJ’s sardonic sense of humour.

Kat: What are you reading now?

Wendy Pollard: The final stages of proofreading, indexing, and book launch events very much interfered with my usual reading habits, and I have a pile of books awaiting me (for which I must thank my daughter who always sends me exactly the ones I have been meaning to buy). Having recently returned from Amsterdam, I am now very much enjoying Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist, and I am looking forward to reading Maggie Gee’s Virginia Woolf in Manhattan.

Kat: Thank you for the interview about your important and fascinating biography. It is one of my favorite books of the year.

As I’ve often said, going to Omaha is like going to Rome for us. Located on the Missouri River, it is the biggest city in a tri-state area. (But no there aren’t seven hills.) Today was a beautiful spring day, so we headed west on the interstate, R.E.M. blaring “Daysleeper.”

“Yeah, ‘Odyssey,”” we said as we crossed the bridge from Council Bluffs to Omaha. I sort of like this spiky metal bridge sculpture, called “Odyssey”: many do not. It looks Western, doesn’t it? I always think of Nebraska as the beginning of the West.

And then we bumped over potholes in a run-down city neighborhood and shortly arrived at the Old Market District, with its charming cobblestone streets, old warehouses, art galleries, antique stores, lawn ornament stores, bars, restaurants, and al fresco dining…

And then we bumped over potholes in a run-down city neighborhood and shortly arrived at the Old Market District, with its charming cobblestone streets, old warehouses, art galleries, antique stores, lawn ornament stores, bars, restaurants, and al fresco dining…

Naturally our favorite place is Jackson Street Booksellers, a huge used bookstore.

It has floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, two big rooms and many nooks and crannies, a few comfortable chairs, and stacks on the floor. Even though it has expanded, there is not enough room on the shelves for all the books. Lots of books by Trollope, Angela Thirkell, Edna O’Brien, Norman Collins, Nicholas Mosley, collectible editions of classics in a box, Black Sparrow Press books, and a beautiful tempting illustrated hardcover of The Yearling. I love this book: it won the Pulitzer in 1939.

I was looking for and found Hermione Lee’s biography of Virginia Woolf: $20. I’m a prudent shopper this spring. Maybe next time.

I was looking for and found Hermione Lee’s biography of Virginia Woolf: $20. I’m a prudent shopper this spring. Maybe next time.

I did buy a lovely first edition of Virginia Woolf’s Flush: $6.

Here are the charming endpages:

There were two copies in the store: this one s a 1933 first Harcourt Brace edition, and the other a nearly identical Book of the Month edition. A Book of the Month Club pamphlet with an essay by Heywood Broun was tucked (mistakenly) inside the book.

There were two copies in the store: this one s a 1933 first Harcourt Brace edition, and the other a nearly identical Book of the Month edition. A Book of the Month Club pamphlet with an essay by Heywood Broun was tucked (mistakenly) inside the book.

But I love it!

There were two stacks of Miss Read books. Any fans? I must admit I’ve never read any of them.

I didn’t make it out of the literature section today. Too bad! They have a good Western history section.

A great day in Omaha!

During my trip to London last year, I explored Bloomsbury.

During my trip to London last year, I explored Bloomsbury.

I am a huge fan of Virginia Woolf. I have read most of her novels, her letters, her diaries, Quentin Bell’s biography, and Leonard Woolf’s autobiography.

In addition to my veneration of Woolf, I have always been fascinated by her painter sister Vanessa Bell.

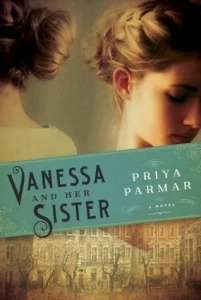

I am reading Priya Parmar’s delightful new novel, Vanessa and Her Sister. Set in London between 1905 and 1912, it is told in the form of Vanessa Bell’s diary, with entries broken up on the page with postcards and letters. Vanessa did not actually keep a diary, but Parmar has created a strong, observant writer’s voice. In addition to running the household, Vanessa worried about the moods of brilliant, unstable Virginia, who had bipolar disorder. Their intellectual brothers Adrian and Thoby knew many artists, critics, and Cambridge intellectuals, among them E. M. Forster, Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, and Duncan Grant. They held Thursday evenings for the group at their house in Bloomsbury.

We learn Virginia has told Vanessa, ““You do not like words, Nessa….They are not your creative nest.” But words are very much her nest, and Vanessa, the only artist in the family, is both practical and precise: her descriptions are very painterly. Here is a stunning excerpt from an entry about their friend Lytton Strachey, the famous biographer.

Lytton. So finely sketched in groups, he can crumple and blur in singular company. I think I prefer the more fractured, muddled Lytton to the clear, quick, brilliant Lytton.

This is also a physically beautiful book. There are replicas of lovely postcards (fictional, of course) from Virginia to her older friend Violet Dickinson, and from Lytton to Leonard Woolf in Ceylon. There are also letters from Leonard to Lytton. There is even a receipt for art supplies delivered to Vanessa.

This novel is as gracefully written as it is captivating.

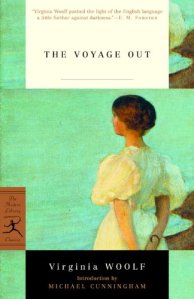

Virginia Woolf has been in the news in the TLS. This month is the 100th anniversary of Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out. At the TLS blog, Thea Lenarduzzi wrote about Woolf’s career as a reviewer at the TLS and how “her responses to the material she was reviewing tell us something, perhaps, about where she was up to” while writing her first novel. You can also listen to Lenarduzzi’s podcast interview with Woolf’s biographer Hermione Lee about The Voyage Out.

Virginia Woolf has been in the news in the TLS. This month is the 100th anniversary of Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out. At the TLS blog, Thea Lenarduzzi wrote about Woolf’s career as a reviewer at the TLS and how “her responses to the material she was reviewing tell us something, perhaps, about where she was up to” while writing her first novel. You can also listen to Lenarduzzi’s podcast interview with Woolf’s biographer Hermione Lee about The Voyage Out.

And, finally, you can participate in a readalong of The Voyage Out sponsored by Behold the Stars and other bloggers. And the blogger Heaven Ali has written a review of The Voyage Out.

It is National Poetry Month!

Edna St. Vincent Millay, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1922, is one of my favorite American poets.

When I was a teenager, I memorized “Recuerdo.” Dried flowers mark this poem in my battered copy of her Collected Poems (or is it a weed?). My friends and I trailed through the woods carrying poetry books, though hiking was a struggle in our fashionable Dr. Scholl’s exercise sandals.

This enchanting poem is evocative not only of the intensity of love but also of her Bohemian identity.

“Recuerdo” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable—

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry;

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry,

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed, “Good morrow, mother!” to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, “God bless you!” for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.