At Barnes and Noble, the last bookstore in our fair city, I was delighted to find a copy of The Odyssey on a “Beach Reads” table. It was a very old translation by George Herbert Palmer, but never mind. I love to imagine a reader picking up Homer for the first time since ninth-grade English, or a freshman Classics in Translation class. I read Greek, so I don’t bother much about translations, but I have seen students inspired by the translations of Lattimore, Fitzgerald, or Fagles.

Epic poems make great beach books, because narrative is as important as the language. It is easy to lose oneself, slathered with sun block under the umbrella, in Homer’s riveting poem about Odysseus’ adventures on the return trip home from the Trojan War, impeded by storms, Cyclops, sirens, and witches. I read and reread Milton’s suspenseful epic rendering of devious Satan’s tempting of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost. It’s a pity so many of us find Satan sympathetic: that was not Milton’s intention. But in Paradise Regained, he is the unreconstructed villain we remember from the New Testament.

Epic poems make great beach books, because narrative is as important as the language. It is easy to lose oneself, slathered with sun block under the umbrella, in Homer’s riveting poem about Odysseus’ adventures on the return trip home from the Trojan War, impeded by storms, Cyclops, sirens, and witches. I read and reread Milton’s suspenseful epic rendering of devious Satan’s tempting of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost. It’s a pity so many of us find Satan sympathetic: that was not Milton’s intention. But in Paradise Regained, he is the unreconstructed villain we remember from the New Testament.

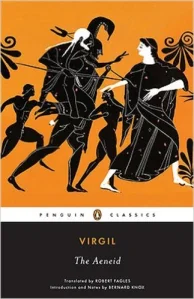

What else would I like to see on that Beach Reads table? Homer’s Iliad, Virgil’s Aeneid, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Derek Walcott’s Omeros,and Alice Oswald’s Memorial. (Let me know your favorite beach epics!)

The best beach epic of all, and possibly the best epic poem in any language, is Virgil’s Aeneid, the story of the founding of Rome by a refugee of the Trojan War. In the essay “What Is a Classic?” T. S. Eliot explains why Virgil’s epic is a “classic”.

A classic can only occur when a civilizsation is mature; when a language and a literature are mature; and it must be the work of a mature mind. It is the importance of that civilization and of that language, as well as the comprehensiveness of the mind of the individual poet, which gives the universality.

Virgil’s sense of history, the maturity of Roman literature, and his knowledge of both Latin and Greek literature gives him a rare command of style, consciousness, and vocabulary. The Aeneid has been read as a celebration of empire; it has also been read as an anti-war poem: there is evidence for both readings. It is a homage to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the texts studied by educated Roman schoolboys. Books I-VI of The Aeneid are about homecoming, or rather about traveling to find their fated home in Italy, and it is loosely based on the Odyssey. Books VII-XII is a story of war, a Roman Iliad: after the Trojan refugees arrive in Italy, Aeneas and his men must fight for the right to stay and Aeneas must marry Princess Lavinia.

Virgil’s sense of history, the maturity of Roman literature, and his knowledge of both Latin and Greek literature gives him a rare command of style, consciousness, and vocabulary. The Aeneid has been read as a celebration of empire; it has also been read as an anti-war poem: there is evidence for both readings. It is a homage to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the texts studied by educated Roman schoolboys. Books I-VI of The Aeneid are about homecoming, or rather about traveling to find their fated home in Italy, and it is loosely based on the Odyssey. Books VII-XII is a story of war, a Roman Iliad: after the Trojan refugees arrive in Italy, Aeneas and his men must fight for the right to stay and Aeneas must marry Princess Lavinia.

Virgil begins the poem:

arma virumque cano…

A literal translation is “arms and the man I sing…”

The first word arma refers to the war described in the last six books. The second word, virum, refers to the man , Aeneas, whom we meet during his trials in the first six books., as The Odyssey is about the man Odysseus. Note that these two words, the subject of The Aeneid, open the poem.

Without knowing anything about Roman culture, it can be tough to understand The Aeneid. I wonder how Seamus Heaney’s new translation of Book VI, in which Aeneas visits the Underworld, fares with the common reader who has not read the entire poem. There is a lot to take in: the homage to the Odyssey, the odd behavior of the Sibyl, the significance of the golden bough, the pageant of the future…

The best bet, even if you decide just to read the Heaney, is to get a copy of Robert Fagles’s translation of The Aeneid for background. First reaason: the whole poem is there. Second Reason: the brilliant Bernard Knox, who was probably as close to a celebrity classicist as the U.S. has ever had, writes the introduction beautifully and succinctly, and intelligently gives you all the background you need. Of pietas, he writes:

Pietas describes another loyalty and duty, besides that to the gods and the family. It is for the Roman, to Rome, and in Aeneas’ case, to his mission to found it in Hesperia, the western country, Italy.

As state budget cuts threaten or slash language departments at public high schools and the state universities where , by the way, the majority of Americans study languages, classics departments bite the bullet and peppily teach culture classes. SUNY Albany eliminated it classics department, along with French, Italian, Russian, and theater. I worry that in the not-so-distant future classics will be yanked from business-oriented curricula and taught only at the most exclusive expensive prep schools and private universities. If that day comes, the division of the rich and poor will be even more exaggerated than now: only the elite will have knowledge of ancient languages and culture. I am not exaggerating: that is our heritage. But Budget cuts are making war on the middle class. Without Latin and Greek, we would be a poorer civilization.

What a delightful cover, Kat! Read The Od at my lovely snob school but none of your other epics/

LikeLike

The Odyssey is so much fun! And Penguin covers are always so attractive.

LikeLike

I’m reading Joyce’s Ulysses with a copy of The Odyssey next to me….two epics!

LikeLike

And I agree with you on the loss of the classics in the job driven revisions of our educational system. We read the greeks in my sophomore class in high school and got a thorough grounding in the myths.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s so much better to get the grounding when you’re young. Latin departments have been eradicated from most high schools (there never was much Greek), so there’s no natural “feed” into classics at universities. It’s so important for readers to know the classics, whether in translation or the original language, and I fear that new teachers don’t know their Homer or Virgil. It may not be deliberate “war” on the middle class (though I often think it is) but the effect of budget cuts is a deprivation of culture.

LikeLike

Oh, how much fun to read them side by side. I missed Bloomsday this year! (Dare I admit I prefer Dubliners to Ulysses?)

LikeLike

You’ve convinced me that if I need a beach read I’ll got for an epic – now if I could only organise a break this summer…. =:o

LikeLike

Yes, working takes up a lot of “epic” time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the UK you can buy George Chapman’s Elizabethan translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey in one huge paperback volume for £3. 95. Mind you, you’d need a very long holiday to read them both. The only flaw is that they didn’t use Keats’s great sonnet – the great argument for learning about foreign cultures through ranslations – as the blurb.

LikeLike

Oh, Chapman’s Homer! I’ve never seen a copy, but why didn’t they include the Keats? I am partial to collecting translations, and there is a Wordsworth edition here. If I see it in a used bookstore…

LikeLike

Pingback: David Ferry’s New Translation of Virgil’s Aeneid – mirabile dictu