I was not aware until recently that women wrote pulp fiction in the 1940s. I associated pulp with the great Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. But women’s pulp fiction has been reissued both in The Feminist Press’s Femmes Fatales series and in a stunning Library of America volume, Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s. Last fall I read Vera Caspary’s unputdownable Laura. Laura, a popular advertising executive, has been murdered, killed by a sawed-off shotgun. The novel is cleverly told from three different points of view, that of Laura, an obese newspaper columnist, and the detective.

I was not aware until recently that women wrote pulp fiction in the 1940s. I associated pulp with the great Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. But women’s pulp fiction has been reissued both in The Feminist Press’s Femmes Fatales series and in a stunning Library of America volume, Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s. Last fall I read Vera Caspary’s unputdownable Laura. Laura, a popular advertising executive, has been murdered, killed by a sawed-off shotgun. The novel is cleverly told from three different points of view, that of Laura, an obese newspaper columnist, and the detective.

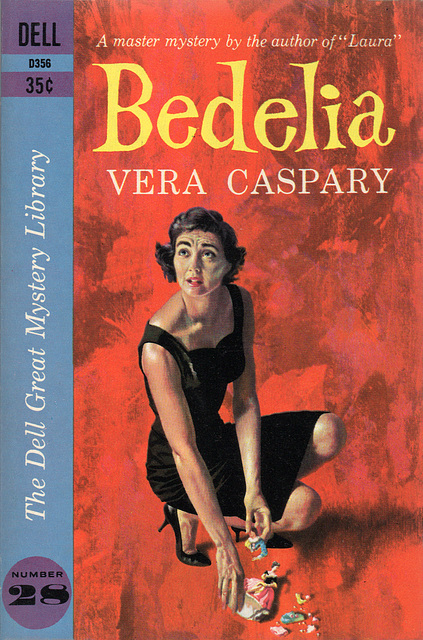

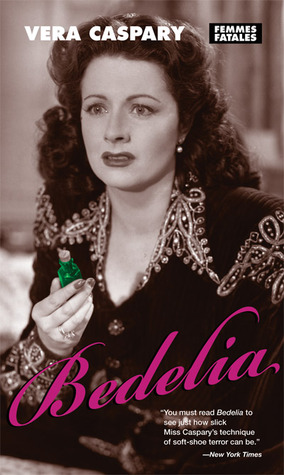

I recently read Vera Caspary’s “domestic suspense”novel, Bedelia,, a gripping story of a mad housewife.

Men love sweet, naive, seductive Bedelia. She and Charlie, a well-to-do architect, are newly married. Bedelia, a widow, met him at a resort in Colorado, where she was recovering from the death of her husband, who she said was an artist in New Orleans.

Set in 1913, the book starts with a Christmas party in Connecticut. Bedelia is excited, and Charlie dotes on her.

This was to be his wife’s first Christmas in Charlie’s house. They had been married in August. She was a tiny creature, lovable as a kitten. Her eyes were lively, dark, and always slightly moist. In contrast with her brunette radiance, Charlie seemed all the more pallid, angular, and restrained.

Although I do not like “kitten” women, the party is wonderful. Bedelia’s decorations and food are delightful. And she has bought expensive, thoughtful gifts for everyone.

There is, however, trouble from the beginning: we suspect she is less naive than she pretends. There is trouble about an artificial black pearl ring,. Charlie doesn’t like artificial jewelry, so he gives her a garnet ring to wear instead and she assures him she has given away the black pearl. It turns she still has the ring. He is frustrated by this deception.

Still, she is lovely. Here is a description of how he views his darling Bedelia’s housewifery skills.

Bedelia had tied over her blue dress an apron as crisp and clean as the curtains. She looked less like a housewife than a character in a drawing-room comedy, the maid who flirts with the butler as she whisks her feather duster over the furniture. The kitchen, with its neat shelves, starched curtains, and copper pots, made Charlie think of a stage-setting. And when Bedelia brought out her red-handled egg-beater and started whipping up a froth in a yellow bowl, he was enchanted. He had to hug her.

Life isn’t all neat and starched, though. Bedelia has terrible nightmares. Really terrible. She won’t sleep unless the light is on. And she communicates her fear to Charlie, so that he, too, becomes paranoid about the dark.

Gradually her fears had infected him. In the daytime he resolved to harden himself against contagion, but when she clung to him in the dark, weeping, his mind filled with strange fancies and his flesh, under the blankets, chilled. By day his wife was earthy, a woman who loved her home and had a genuine talent for housekeeping. In the dark she seemed entirely another sort of creature, female but sinister, a woman whose face Charlie had never seen. It was absurd for a man of his intelligence to let himself be affected by these vague and formless fantasies, and he tried to account for his wife’s fear of the dark by remembering that she had lived a hard life.”

Bedelia becomes more and more tightly wound, especially about their artist neighbor, Ben. Charlie wonders on earth has happened to his wife. We become suspicious.

Well, I don’t want to tell you too much, but I will tell you this: things are not what they seem. I couldn’t stop reading it! It is not as good as Laura,–I thought the ending was a little weak–but I enjoyed it very much.

I do intend to read more Caspary, and if anyone has recommendations, I would love to hear them.