I don’t like to be classical when there’s a turkey in the oven.

I don’t like to be classical when there’s a turkey in the oven.

And so I read middlebrow novels on Thanksgiving.

One year it was Edna Ferber’s Giant, a bold novel about an intellectual Southern woman who marries a rich Texas rancher. (Ferber won the Pulitzer for her masterpiece, So Big.) On another, it was Jacqueline’s Susann’s page-turner, Valley of the Dolls, the story of three friends in New York who succeed as a model, a singer-actress, and actress, but two tragically turn to drugs.

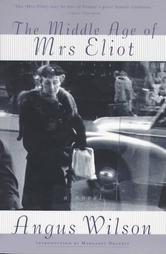

Not everyone would agree that Angus Wilson’s The Middle Age of Mrs. Eliot is middlebrow. Indeed, he is a much more literary writer than either Ferber or Susann. This fast-paced, intelligent novel, published in 1958 and winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, is often elegantly-written, and misses being a classic by a hair. But the characterization is sometimes unbelievable, the writing seems dated, and there is a hint of misogyny in Wilson’s portrait of Mrs. Eliot. He also chronicles the middle age of her much less interesting homosexual brother, David.

The heroine, Meg Eliot, has the perfect life. She is the wife of a rich lawyer, gives marvelous parties, and dominates the “Aid to the Elderly” committee she insists on chairing for an unprecedented third time. Before she leaves on a six-month trip around the world with her husband, she firmly forbids punitive measures like depriving a very old woman of her gin.

The heroine, Meg Eliot, has the perfect life. She is the wife of a rich lawyer, gives marvelous parties, and dominates the “Aid to the Elderly” committee she insists on chairing for an unprecedented third time. Before she leaves on a six-month trip around the world with her husband, she firmly forbids punitive measures like depriving a very old woman of her gin.

Meg is wound up because she is also giving a big going-away party. She feels empty as she waits for her husband Bill to come home.

There was nothing for it but to seek the escape she and David had found in the past. Emma, The Mill on the Floss, The Small House at Allington, The Portrait of a Lady lay together with her hand luggage.

Reading holds her together, and, by the way, she compares herself to Emma and Maggie Tulliver.

Theparty is a success: even her “lame duck” friends mill and throng, while Bill and his friends play bridge. But Bill has been uneasy about his health, and seems unsettled. On the plane to Asia, he makes a special effort on her behalf, and reads a bit of The Portrait of the Lady, but it doesn’t interest him.

Then, during an hour-long stop at an airport restaurant in Badai, Meg teases him about his criticism of the younger generation, and Bill tactlessly refers to her infertility. Meg, terribly upset, goes to the lavatory to pull herself together. While she is gone, he is killed by an assassin’s bullet aimed at a high-ranking official. Although he is hailed as a hero, Meg believes it was an accident.

Meg has a mental breakdown. When she finally gets home to London, she discovers that Bill had no money. Meg’s confidence has been that of a trophy wife, and she seems, not surprisingly, unable to survive without Bill.

How she starts over–the secretarial course, staying in sordid hotels, and eventually alienating her best friends–is not the story we expect.

Her homosexual brother David, whose partner, Gordon, has just died of cancer, runs a nursery where he deals paternalistically with an odd menage of employees. He is cold, repressed, and irritable, and does not want Meg to stay with him, but it is inevitable.

There’s a hint of misogyny in the portrait of Meg, but in the introduction Margaret Drabble says,

…it has a powerful effect on a generation of women readers, including myself. It was the kind of book which needed to exist, and it occupied a space which was waiting for it. It is now hard to recall, after three flourishing decades of female and feminist fiction, the dismal and stereotypical portrayals of women which was on offer in the early post-war period…

I am not of that generation of readers. This novel is, however, very entertaining, and if it were not in print, would have Virago potential.

Intriguing – I’ve never read Wilson but I have a sneaking suspicion there *may* be one of his books in the house!

LikeLike

I know he is very well-thought of, and it may be that this is not his best book. I was, however, glued to it!

LikeLike

I read a couple of novels by Angus Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Attitudes and ‘Late Cal” but would not call either of them Middlebrow. ‘Anglo-Saxon Attitudes’ was a humorous campus novel. He is one of those writers in danger of being forgotten.

LikeLike

My guess is that this is not his best book. There is some fine writing, but it’s essentially literary fiction gone to the melodramatic bad. He’s a little shrill in his depiction of the Mrs. Eliot, who becomes thoroughly unlikable, almost monstrous in her hysteria, as the novel continues. I did read Anglo-Sax Attitudes years ago and enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Angus Wilson’s Late Call – mirabile dictu