On a recent trip to London, I was in and out of used bookstores. I am always intrigued by the many English books not available in the U.S. I bought mainly paperbacks, so as to be able to fit them into my luggage, which eventually expanded to include a Waitrose shopping bag. “Ma’am, you’re going to have to keep that under the seat,” the flight attendant said.

One of my best finds was an old Penguin copy of Angus Wilson’s 1964 novel, Late Call. As far as I can tell, Late Call was never published in the U.S. There may be a reason for this: it is set in one of the New Towns in England, and do we know what a New Town is? As is often the case, I kind of got it as I read. But for the sake of efficiency, I will quote Wikipedia: “The new towns in the United Kingdom were planned under the powers of the New Towns Act 1946 and later acts to relocate populations in poor or bombed-out housing following the Second World War.”

This strange novel is partly serious, partly satiric. I very much liked it on the realistic level, as the story of an old woman adjusting to retirement. The heroine, Sylvia Calvert, a manageress of a hotel, retires in her early sixties because of high blood pressure (not to mention complaints about her husband, Arthur, who loses money at cards and borrows from the residents). Sylvia longs to start a new life, living with her son Harold and his children in Carshall New Town, but it proves to be a difficult adjustment: in a matter of days she goes from being a respected woman in charge of a business to an old woman not even trusted with the housework. Her son Harold, the insufferable headmaster of a secondary modern, insists on making a roster of household tasks for the whole family. (That seems very ’60s and early ’70s to me: feminists in collectives and co-ops always had housework schedules.) And so Sylvia would really like to do all the housework and cooking, but has little responsibility. The only person who doesn’t have chores is Arthur, out playing cards all day.

Living with the obnoxious Harold is a nightmare. He is condescending to Sylvia, and preaches endlessly about the superiority of the way of life in Carshall. He likes the rigid plan of the town, and is proud of his own modern house. The ultra-modern ugly kitchen, which he and his late wife Beth designed for efficiency, has so many electric gadgets that he must lecture and quiz Sylvia on them. She doesn’t have the faintest idea what he is talking about.

Living with the obnoxious Harold is a nightmare. He is condescending to Sylvia, and preaches endlessly about the superiority of the way of life in Carshall. He likes the rigid plan of the town, and is proud of his own modern house. The ultra-modern ugly kitchen, which he and his late wife Beth designed for efficiency, has so many electric gadgets that he must lecture and quiz Sylvia on them. She doesn’t have the faintest idea what he is talking about.

Harold looked at her. “You’re like Rip Van Winkle, Mother…. Now, we must concentrate on the job in hand. What do you do with the autotimer? Think now, Sylvia.” He’d never used her Christian name; and although it was meant to be some kind of joke, she felt most uncomfortable. However she must try to play up to him. Some vague, long forgotten memory of school came back to her: it spelt ‘catch.’ She would not be caught.

Sylvia wants to stay home and read and watch TV, but he thinks she should keep busy, so gets his friends to give her work as a volunteer secretary for a save-the-meadow campaign. (And the meadow is ugly! but Harold is obsessed with the preservation). Sylvia is exhausted by the job, and then her pleasure in historical novels is ruined because her pseudo-employer mocks her for reading them. (And so Sylvia turns to the genre true crime.)

Sylvia wants to stay home and read and watch TV, but he thinks she should keep busy, so gets his friends to give her work as a volunteer secretary for a save-the-meadow campaign. (And the meadow is ugly! but Harold is obsessed with the preservation). Sylvia is exhausted by the job, and then her pleasure in historical novels is ruined because her pseudo-employer mocks her for reading them. (And so Sylvia turns to the genre true crime.)

While Sylvia is trying to read, Harold becomes increasingly obsessed with the meadow, and his children fall apart with problems he doesn’t notice. His son, Ray, a charming gay man, is terrified of being outed in Carshall (Sylvia doesn’t know anything about homosexuality, but she is completely on her grandson’s side). Long-haired Mark is a CND supporter whose radical causes annoy Harold: why can’t Mark just save the meadow? And Judy, a snobbish teenager, spends most of her time with horse-owing “county” people, though she really wants Harold’s attention.

Sylvia loves her grandchildren, but this modern family is not enough for her. And so she begins a series of long walks. It very hard to get out of Carshall: all the trails are carefully designed to lead back there. And so freedom for Syliva is about escaping from the New Town. She finds the one trail that leads to the country, and a friendship with outsiders, a farmer’s American wife and her daughter, help her get her identity back. But while Sylvia is enjoying herself, the whole family is falling apart.

Wilson’s satire of Harold is so effective that I was surprised and disappointed to be told at the end that he is having a breakdown. Breakdown or no, he is odious, as are most of his friends in town. Wilson doesn’t make him more likable, but we are supposed to see him as a more realistic character, I suppose. But I really felt that Harold was characteristic of the New Town, and now I have to like him? Isn’t this a satire of the New Town? I need an introduction in an American edtiion.

Wilson’s style is lively and satiric, and the book is very entertaining! I raced through this. And yet I needed one or two notes…

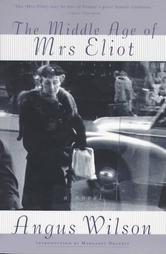

Margaret Drabble wrote a biography of Wilson, and I would love to read it. A few years ago I read and very much enjoyed Wilson’s novel, The Middle Age of Eliot. I wrote here, “This fast-paced, intelligent novel, published in 1958 and winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, is often elegantly-written, and misses being a classic by a hair.” Anglo-Saxon Attitudes is also in print, published by NYRB. Any recommendations of other books by Wilson?