God bless the state universities! Without education for the people, this particular Iowa City girl might never have read Pushkin. I went to college on Pell grants, loans, and part-time jobs, and had to sell my books to buy tampons, but who didn’t? It only took seven years’ working at a poverty-level job to repay the loans. Here’s a little secret they don’t share with Millennials: the economy back then was terrible, too.

One of the best reasons to go to the university: you can read Pushkin as part of your work. I loved Eugene Onegin, a playful novel in verse, and enjoyed a few of the stories, though not as much.

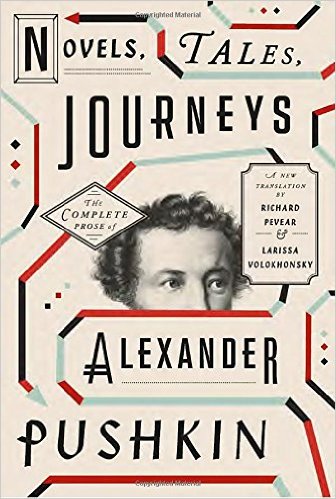

At the Barnes and Noble Review, Heller McAlpin writes about a new translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Novels, Tales, Journeys: The Complete Prose of Alexander Pushkin. Mind you, I don’t have the new book but I got out my trusty Everyman edition, The Collected Stories, translated by Paul Debreczeny.

New edition of Pushkin’s prose.

McAlpin hopes that Pevear and Volokhonsky’s lively new translation will help new readers discover Pushkin, but has compared translations and does not find them very different. He writes,

In the brief introduction to her translation of my well-worn Everyman edition of The Captain’s Daughter and Other Stories, Natalie Duddington wrote, “As a poet, Pushkin is untranslatable: the exquisite beauty and the austere simplicity of his verse cannot be rendered into a foreign tongue . . . But his prose has none of this poetic quality and loses but little in translation. It is vigorous and straightforward and sounds as simple and natural today as it did a hundred years ago.”

Clearly, prose is easier to translate. So it’s not surprising that a comparison of Pevear and Volokhonsky’s new edition with earlier translations — by T. Keane, Rochelle Townsend, and Natalie Duddington — reveals just minor differences: “gloomy Russia” becomes “sad Russia,” “the damned Frenchman” becomes the more humorous “that cursed moosieu.” More salient is the title of Pushkin’s frustratingly unfinished novel based on his great-grandfather Ibrahim Gannibal: The Moor of Peter the Great instead of the more common The Blackamoor of Peter the Great or Peter the Great’s Negro. Despite the avoidance of the racial epithet, none of the ironic edge of this comment is lost in translation: “Too bad he’s a Moor, otherwise we couldn’t dream of a better suitor.”

And so I quickly fell into my book. The first narrative, The Blackamoor of Peter the Great, is based on the story of Pushkin’s maternal grandfather, an African who was taken hostage as a boy and purchased for Peter the Great, who raised him as his godson. In Pushkin’s fascinating story of the relationship between the czar and the hero, Ibrahim, a handsome, charming black man, Pushkin explores attitdues toward race. In Paris, Ibrahim is eventaully accepted, to the point that his color is almost forgotten, partly because he attracts women, and he has an affair with a duchess. But when the czar writes wishing his godson were bakc in Russia, Ibrahim dutifully deserts his Duchess and goes to Petersburg, where he works very hard for the brilliant czar. But ironically this relationship does not guarantee the Russians’ acceptance of Ibrahim in society. An aristocratic family resists the czar’s suggestion of a marraige between Ibrahim and their duaghter.

And then suddenly the story ends, six paragraphs into Chapter 7, and I thought I’d gone out of my mind.

So I skimmed the introduction and learned The Blackamoor of Peter the Great is an unfinished novel.

And now I’m haunted by the characters and will never know what happens.

I do wish the fragments were labeled as such in the contents. I read a sample of the new translation by Pevear and Volokhonsky, and the introduction is better organized. There are other prose fragments as well.

Here are a few sketchy notes about why you should read Pushkin.

- Pushkin established intimacy between the reader and writer. Explored basic themes of maturation and metamorphosis.

- Pushkinesque–opposed to romantic–clear, spare; few similes, metaphors, metonymic style, contiguity, evocative.

- Pushkin played with form. More natural prose.

- Attempt at psychological fix. The beginning of realism for Russian novel.

Okay, you’re just going to have to read an introduction, because I’m done!

I read his Belkin’s Tales a while back and loved them – wonderful stories. I don’t think I’d go for the new translation you mention, but I have a nice lot of his works on my shelf. Obviously time to pick him up again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pushkin is so much fun. I’d forgotten how much fun, so it’s good a new translation has been published, even though I’m reading an old one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I, too, read Pushkin at university. The Tales of Belkin and Eugene Onegin and his other poetry were just wonderful. The opera of Eugene Onegin is worthy of Pushkin too. Tatiana’s letter scene is a real tour de force.

LikeLike

He is stunning! I know why he’s the father of Russian literature.

LikeLike

I just ordered the new one from the library. Surprisingly they had very few of his books. I’ve never read him.

LikeLike

Cynthia, I’m sure the new one is worthwhile! I love the Everyman edition, but there are several fragments, not labeled as fragments, and I had to go back and hunt through the introduction, which was very annoying. Pevear and Volokhonsky will have footnotes and make everything clear.

LikeLike

I was also frustrated by the abrupt ending of “the Moor of Peter the Great” but it still was one of my favourites. In the end I decided that it probably would have continued more or less as the life of Abram Petrovich Gannibal (as told by Wikipedia), with a bad marriage followed by a happy one. Perhaps with a Swedish woman (like Pushkin’s great-grandmother) related to the Swedish captive officer we met.

LikeLike

I do love Pushkin! Yes, it might very well go like that. Somebody should finish it, the way they do Jane Austen’s unfinished work (only un-Austenish, of course_.

LikeLiked by 1 person