The Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing (1919-2013) had a powerful effect on my thinking as a young woman. I started with The Golden Notebook, her experimental novel about “free women” (as she ironically says) and the breakdown of personality. In her early novels, Lessing illuminated aspects of women’s sexuality, radical politics, marriage, and the nuclear family. Later, she wrote experimental novels and science fiction about the consequences of war, nuclear power, pollution and the disintegration of society.

The Nobel Prize winner Doris Lessing (1919-2013) had a powerful effect on my thinking as a young woman. I started with The Golden Notebook, her experimental novel about “free women” (as she ironically says) and the breakdown of personality. In her early novels, Lessing illuminated aspects of women’s sexuality, radical politics, marriage, and the nuclear family. Later, she wrote experimental novels and science fiction about the consequences of war, nuclear power, pollution and the disintegration of society.

I recently reread Martha Quest, the first in her autobiographical five-book Children of Violence series. This series is Lessing’s masterpiece, truly representative of the wide range of her work. Written over 17 years (1952-1969), it has held up better even than The Golden Notebook, and it surpasses much of her later work. It is a bildungsroman: the first four books, set in Africa, are conventional novels. Lessing traces the history of the heroine, Martha Quest, from adolescence on an African farm to her years as a young woman in a small African town, where she works as a secretary, marries disastrously twice, and then becomes involved with a communist group. In the last book, The Four-Gated City, an experimental novel, Lessing follows Martha to London at 30.

Last year when I reread The Children of Violence, I skipped the first book, Martha Quest. And, having just reread it, I understand why. In this realistic novel, Lessing’s description of the destructive relationship between Martha and her mother is very painful. The generational divide is unbridgeable.

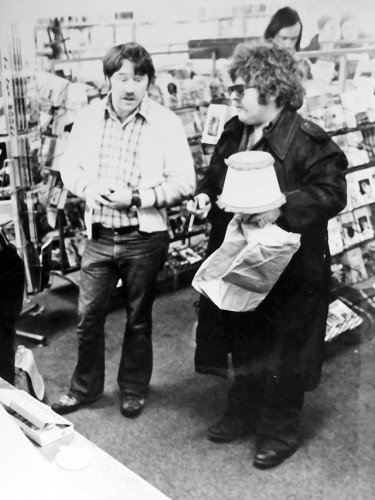

Doris Lessing in 1949, just before she left for London.

When the book opens on the African farm, Martha, a 15-year-old dropout, is irritably reading Havelock Ellis on sex, while her mother, a former English nurse, gossips on the veranda with Mrs. Van Rensberg, a Dutch housewife. The Quests consider themselves superior to the Van Rensbergs, and Martha feels guilty about it, but she considers both families equally hypocritical, especially the women: Mrs. Quest denies Martha’s maturity even though she is bursting out of her childish clothes, while Mrs. Van Rensberg lets her daughter Marnie dress in the latest fashions and hopes to marry her off as soon as possible.

Since women’s conversation doesn’t suit Martha, her main social contact is with the radical Jewish Cohen brothers, who live in the village where their father has a store and lend her books. She reads everything: English novels and poetry, books on politics, sexuality, and psychology. But the cultural abyss between literature and the reality of life on a farm in Zambesia (a fictional country in Africa) is enormous. She doesn’t read about any young women who rebel against their parents as she does.

What fascinates me is the way Lessing interweaves ideas and questions with the narrative.

…she was seeing herself, and in the only way she was equipped to do this—through literature. For if one reads novels from earlier times, and if novels accurately reflect, as we hope and trust they do, the life of their era, then one is forced to conclude that being young was much easier then than it is now. Did X and Y and Z, those blithe heroes and heroines, loathe school, despise their parents and teachers who never understood them, spend years of their lives fighting to free themselves from an environment they considered altogether beneath them? No, they did not; while in a hundred years’ time people will read the novels of this century and conclude that everyone (no less) suffered adolescence like a disease, for they will hardly be able to lay hands on a novel which does not describe the condition. What then? For Martha was tormented, and there was no escaping it.

I find this fascinating, because I gather (perhaps erroneously) that mother-daughter relationships are smoother than they used to be. In my day, we were not only dying to leave home, but to leave our hometown as soon as possible! (It took me a while, as it did Martha.) So will the literature of this century reflect an entirely different set of beliefs?

I find this fascinating, because I gather (perhaps erroneously) that mother-daughter relationships are smoother than they used to be. In my day, we were not only dying to leave home, but to leave our hometown as soon as possible! (It took me a while, as it did Martha.) So will the literature of this century reflect an entirely different set of beliefs?

Martha has to rebel and fight her mother to be herself. Everything becomes a battle. She gets a ride to town and buys cloth at the Cohens’ store and begins to make her own dresses, though her mother forbids her to and screams at her for spending her father’s money. She is not allowed to walk to or from town, so her father, an invalid, finally intervenes and occasionally take her side. Eventually he suggests she move to town, because he can’t stand the fighting, and Martha is hurt. But when the Cohens find her a secretary job at their uncle’s law firm, Martha is elated.

But she cannot be true to herself. Soon she goes every night to sundowner parties, drinks too much, and gets too little sleep. Donovan, a closeted gay man, escorts her to restaurants and the sports club, and teaches her how to dress. At the sports club she dances with many beefy men, who admire her and moan, “Oh, baby, you’re killing me.” When Marnie Van Rensberg shows up and they shower attention on her, Martha is jealous, but then she realizes that the newest girl always gets the attention.

And Stella, a beautiful Jewish woman married to handsome Andrew, takes Martha under her wing and insists on bringing her and the man of the moment back to her flat. Martha becomes afraid to be alone. She is exhausted–she seldom sleeps more than a few hours a night– and finally has to call in sick for a few days so she can read and recover herself. But then she becomes entangled once again with Stella and the club, and when she meets Douglas Knowell, an intelligent, kind man who also reads The New Statesman, she falls, if not in love, in like.

Martha has always said she would rather die than be conventional. She doesn’t want to marry or have children.

If someone had asked her, just then, if she wanted to marry Douglas, she would have exclaimed in horror that she would rather die.

But Martha cannot be the person she wants to be yet. She is young, she is silly, and she is caught up with a crowd.

And that’s what it’s like to be a young woman, isn’t it? It takes a while to be yourself.

Allison Winn Scotch’s new novel, In Twenty Years, is my favorite beach book of 2016. It has a lot in common with Emma Straub’s widely-reviewed light novel, Modern Lovers. Both center on the midlife crises of a group of old college friends–and, coincidentally, one of the group members in each book is a rock star.

Allison Winn Scotch’s new novel, In Twenty Years, is my favorite beach book of 2016. It has a lot in common with Emma Straub’s widely-reviewed light novel, Modern Lovers. Both center on the midlife crises of a group of old college friends–and, coincidentally, one of the group members in each book is a rock star.

When her husband flushes her birth control pills down the toilet, she runs away to Boston and changes her name. She reads widely and gets to know some interesting peoplein a commune. When she tires of the power struggles between the men and women, she starts her own commune for women. They want to form an identity outside the world of the nuclear family and consumerism. At night they do improvisational theater.

When her husband flushes her birth control pills down the toilet, she runs away to Boston and changes her name. She reads widely and gets to know some interesting peoplein a commune. When she tires of the power struggles between the men and women, she starts her own commune for women. They want to form an identity outside the world of the nuclear family and consumerism. At night they do improvisational theater.