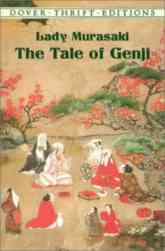

Genre fiction is popular, but it is still not quite the thing among the literati. In order of acceptability, we have (a) mysteries, (b) historical fiction, (c) SF, and (d) romance.

SF is the most daring of the genres, but has long been considered a bastard child of literature, perhaps because it depends on “world-building” rather than corpses, Henry VIII, or flirting with guys with waxed chests. It’s fairy tales, it’s epic, it’s tragedy, it’s fantastic voyages, and it’s medieval romance, but with robots and dragons, which doesn’t always go over well. Critics praise SF founders Jules Verne and H. G. Wells but have skipped over many stunning later SF classics.

In recent years, however, I have noticed that science fiction and fantasy have become more visible in literary publications. It may be solely because of George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones series. Why? Male critics John Mullan (The Guardian), John Lanchester (The London Review of Books), Daniel Mendelsohn (The New York Review of Books), and Tim Martin (The Telegraph) have compared the series to Shakespeare’s history plays and Lord of the Rings. Fans, especially men, have gone mad for it.

I very much enjoyed the first volume of Martin’s series, Game of Thrones, and if it brings people to SF/fantasy, I’m all for it. What the critics don’t seem to realize is that other SF writers are equally well-acquainted with Shakespeare, history, and classics. For instance, the award-winning Jo Walton and C. J. Cherryh both have classics degrees. Pamela Dean, author of the masterpiece, Tam Lin, has a master’s in English. The genre-bending David Mitchell, twice nominated for the Man Booker Prize, has a master’s in comparative literature.

I very much enjoyed the first volume of Martin’s series, Game of Thrones, and if it brings people to SF/fantasy, I’m all for it. What the critics don’t seem to realize is that other SF writers are equally well-acquainted with Shakespeare, history, and classics. For instance, the award-winning Jo Walton and C. J. Cherryh both have classics degrees. Pamela Dean, author of the masterpiece, Tam Lin, has a master’s in English. The genre-bending David Mitchell, twice nominated for the Man Booker Prize, has a master’s in comparative literature.

Sure, some SF writers write formula fiction, but the best SF writers take big chances. Not only do they create a viable future or fascinating alternate history, but some criticize the consequences of political and sociological trends. In Stand on Zanzibar, John Brunner describes the fragmentation of society in a postmodern narrative broken up by quotations from radical sociologist Chad Mulligan (who is rather like Marshall McLuhan), news blurbs, and rumors on something called “Scanalyzer.” (There is even, bizarrely, an African president named Obami: pretty close to reality, right?) Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, another post-modern classic, is an SF lyrical Ulysses set in a city that has survived an unspecified disaster. Philip K. Dick’s alternate history, The Man in the High Castle, explores what might have happened in the U.S. if the Nazis had won. All of them are brilliant writers.

But what about new SF? I recently discovered Ann Leckie’s fascinating novel, Ancillary Justice, which in 2014 won the Hugo Award, the Nebula Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the BSFA Award. That’s quite a sweep. And it’s the first of a trilogy.

But what about new SF? I recently discovered Ann Leckie’s fascinating novel, Ancillary Justice, which in 2014 won the Hugo Award, the Nebula Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the BSFA Award. That’s quite a sweep. And it’s the first of a trilogy.

Is it an SF classic? Yes. It is a beautifully-written first novel, a very fast read, and parts are brilliant. I loved it from the opening pages. The narrator, Breq, a soldier who has trouble identifying gender, is in search of a very specialized antique on a dangerous trip to a cold, isolated wintry planet. (A nod to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness.)

The book opens like a noir western (if there is such a thing). Breq finds a body in the snow. Somehow it looks familiar.

Sometimes I don’t know why I do the things I do. Even after all this time it’s still a new thing for me not to know, not to have orders to follow from one moment to the next. So I can’t explain to you why I stopped and with one foot lifted the naked shoulder so I could see the person’s face.

Frozen, bruised, and bloody as she was, I knew her. Her name was Seivarden Vendaai, and a long time ago she had been one of my officers, a young lieutenant, eventually promoted to her own command, another ship. I had thought her a thousand years dead, but she was, undeniably, here. I crouched down and felt for a pulse, for the faintest stir of breath.

And so Breq rescues Seivarden, whose body was frozen for 1,000 years after a disaster and recently rediscovered and thawed. Seivarden is now a drug addict who will sell anything she can find for drugs. But Breq understands the tragic history of the unlikable Seivarden only too well: she refused “re-eduaction” and turned to drugs after she was suddenly awakened and found herself in a world she didn’t understand. Breq never liked Seivarden, and yet she can’t let this victim of the past go. It is a thankless job. And yet they form a strange alliance.

Breq has business with a doctor/antique dealer, who can’t cure addiction but gives medical treatment to Seivarden. It turns out Seivarden is a man (which we promptly forget, since Breq refers to everyone as “she, but it is a revelation: I am surprised by how differently I regard her when I learn she is a man..). Breq’s purpose on this planet is to buy the doctor’s special gun, made by aliens. At first the doctor pretends she doesn’t have it, but Breq has done her homework: 24 of the 25 guns have been recovered, and the doctor is the collector who vanished.

Why does Breq need the gun? Gradually, through a beautifully-written unfolding of the story that is at first bewildering, we learn that she is not human but AI, with a revenge mission. She used to be the central intelligence of a ship, Justice of Toren, or rather one of the ship’s hundreds of ancillary soldiers. Ancillaries are human corpses, surgically rebuilt with implants and made into obedient soldiers to the ships and their human officers. Their brains are connected to each other’s and the ship’s, until a catastrophe tears Breq from the others and she is forced to act as an individual.

Sound complicated? It is. But it is the quality of Leckie’s writing and the vivid characterization that keeps us reading as much as the storytelling. Breq is an incredibly sympathetic character. And she wins the loyalty of Seivarden. After killing for 1,000 years or more, it turns out she can’t stop saving lives.

What a fantastic novel! And I hear the next in the series is even better. This is SF, in the tradition of the great C. J. Cherryh.

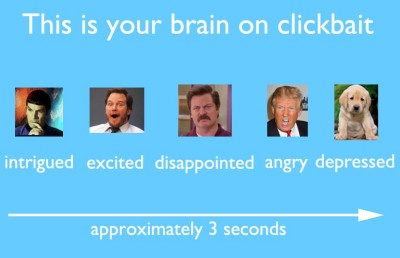

We’re pretty much under the radar at Mirabile Dictu. Clickbait wouldn’t work here: there aren’t enough readers. Heavens, I get complaints if I “disrespect” Jane Austen, which I don’t do, but which someone thought I did. I don’t sell ads–it’s too much trouble to be an Amazon associate and add book links to Amazon, on top of all the scribbling I do. Anyway I’m only a one-woman operation and “review”only a couple of books a week. The rest of the time I’m writing about vaguely bookish topics that don’t sell anything except whether I heart (or don’t heart )reveiwers/writers/ bloggers, depending on what I’m saying.

We’re pretty much under the radar at Mirabile Dictu. Clickbait wouldn’t work here: there aren’t enough readers. Heavens, I get complaints if I “disrespect” Jane Austen, which I don’t do, but which someone thought I did. I don’t sell ads–it’s too much trouble to be an Amazon associate and add book links to Amazon, on top of all the scribbling I do. Anyway I’m only a one-woman operation and “review”only a couple of books a week. The rest of the time I’m writing about vaguely bookish topics that don’t sell anything except whether I heart (or don’t heart )reveiwers/writers/ bloggers, depending on what I’m saying.

Allingham explores the ethics of a murder investigation. They track one of the suspects to France, and when they meet up with Joan and Norah there, W. T. says there is no choice bu tto investigate them further. Jerry is upset: he wants his father to leave Norah alone and asks, “What does it matter who killed him?”

Allingham explores the ethics of a murder investigation. They track one of the suspects to France, and when they meet up with Joan and Norah there, W. T. says there is no choice bu tto investigate them further. Jerry is upset: he wants his father to leave Norah alone and asks, “What does it matter who killed him?”

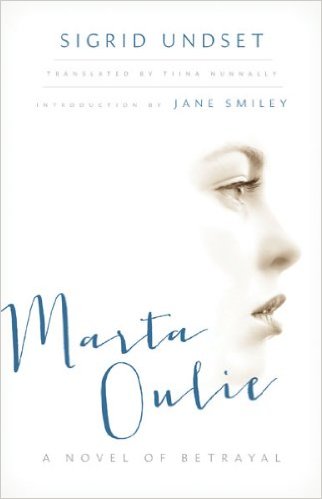

Sigrid Undset, who won the Nobel Prize in 1928, is best known for her brilliant historical trilogy, Kristin Lavrandsatter, and The Master of Hestviken tetralogy. I recently reread Kristin Lavransdatter, one of my favorite books of all time. (I wrote about it

Sigrid Undset, who won the Nobel Prize in 1928, is best known for her brilliant historical trilogy, Kristin Lavrandsatter, and The Master of Hestviken tetralogy. I recently reread Kristin Lavransdatter, one of my favorite books of all time. (I wrote about it  In both stories, a marriage begins happily, but becomes boring to the women. Both heroines (Marta and Tolstoy’s Masha) tire of their constricted lives. Marta, a teacher, is restless. She was very much in love with Otto when they married, but after her second child she needed something else.

In both stories, a marriage begins happily, but becomes boring to the women. Both heroines (Marta and Tolstoy’s Masha) tire of their constricted lives. Marta, a teacher, is restless. She was very much in love with Otto when they married, but after her second child she needed something else. I know, I know: you don’t expect me to wrtie about Goodreads. I trashed it at this blog once. But I am now a full-fledged gladiator of the consumer culture. “We who are about to read salute you!”

I know, I know: you don’t expect me to wrtie about Goodreads. I trashed it at this blog once. But I am now a full-fledged gladiator of the consumer culture. “We who are about to read salute you!” I gave 4 stars to Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils.

I gave 4 stars to Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils. The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis, John Banville (Introduction)

The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis, John Banville (Introduction)