“The destruction of Dresden was my first experience with really fantastic waste. To burn down a habitable city and a beautiful one at that … I was simply impressed by the wastefulness, the terrible wastefulness, the meaninglessness of war.”–Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. in 1979.

We live in a violent culture. Wars, shootings, bombings…

How do we cope? Most of us can’t. So we don’t think about it, we knit, cook, and go to movies, and occasionally anti-war classics become comfort reads. Here is a brief look at two anti-war novels by Kurt Vonnegut and Pat Murphy, followed by a short list of anti-war books.

No anti-war list would be complete without Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 novel, Slaughterhouse Five. This satiric novel, immensely popular in the ’60s among draft dodgers and anti-Viet Nam War activists, is his best-known, if not his best book. In the opening chapter, Vonnegut says that he has tried for 23 years to write a novel about the fire-bombing of Dresden, which he witnessed as a prisoner of war and survived because the Germans locked the prisoners in a slaughterhouse at night. He points out that nearly twice the number of people died in Dresden as in Hiroshima.

We read Vonnegut not for his style but for his unusual point of view and inimitable wise-guy voice. He begins,

All this happened, more of less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed the names.

All this happened, more of less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed the names.

At the end of Chapter One, Vonnegut claims the novel is a failure. But it is not: it segues into the story of the anti-hero, Billy Pilgrim, an ineffectual optometry student drafted in World War II and then imprisoned by the Germans. This improbable soldier has other problems, too: he has become unstuck in time: his time travel takes him to Ilium, New York, his hometown, Dresden, and the planet Tramaldore, where all events are simultaneous and he says he has witnessed his death. Billy is a huge fan of the science fiction writer, Kilgore Trout (who appears in several of Vonnegut’s novels), and his contact with Trout may be part of the problem. Psychiatrists think Billy is crazy. But is he?

I plan to reread some Vonnegut this year and will get back to you.

******************************************************************

Pat Murphy

I recently read Pat Murphy’s stunning anti-war novel, The City, Not Long After.

Murphy is an award-winning science fiction writer who won the Nebula Award for The Falling Woman, which I wrote about here, and founded the James Tiptree, Jr. Award for promoting gender awareness in science fiction, with Karen Joy Fowler.

The City, Not Long After, published in 1989, takes place after the Plague destroys civilization.

San Francisco is now a ghost city, inhabited mainly by artists and a few very smart librarians. But Mary Laurence, a former peace activist from San Francisco who blames herself for the plague, leaves the city and gives birth to her daughter in an abandoned farmhouse. She is in such pain that she screams at the ghost of her husband to help her. An angel comes instead, and offers to help if she can name the baby. But sixteen years on the naming still hasn’t happened. And so her daughter, the heroine, is referred to as “Daughter’ or, later, simply “the woman,” because the angel still hasn’t named her.

The woman, clearly a predecessor of Catniss in The Hunger Games (perhaps Suzanne Collins read this), learned to make snares, slingshots, and a cross-bow from studying the weapons article in an encyclopedia, and has helped her mother survive. She also becomes fascinated by San Francisco after finding a snow globe containing a miniature San Francisco.

As if the plague and fevers weren’t bad enough, a new warmonger, General Fourstar, wants to establish “order” in the West, and after he arrests her mother for entertaining a book dealer (books are outlawed by the army), Mary catches a fever. When she is dying she claims she is going to San Francisco, and makes her daughter promise to follow with the news of Fourstar’s planned invasion. The woman thinks Mary is delirious, but then she sees a flash of the angel.

And so she goes to San Francisco with news of the war, but also to find her mother.

Murphy’s style is simple but effective. Here is a description of the woman’s first sight of San Francisco.

Murphy’s style is simple but effective. Here is a description of the woman’s first sight of San Francisco.

The woman looked toward San Francisco and doubted, for the first time, the wisdom of her journey. Looking at the city in her glass globe, she had not dreamed that it would be so large and so strange. She thought for a moment of returning to the valley, where she knew the best places for hunting, the groves where quail nested, the meadows where deer came to graze. She shook her head and spurred her horse onward, following the ribbon of freeway.

After they fully understand what the General wants, the artists plan to fight a war without violence., with art installations. The descriptions of the art installations are gorgeous.

It’s a lovely little book.

AND A SHORT ANTI-WAR LIT LIST (and please let me know your own favorites):

- Joseph Heller’s Catch-22

- Homer’s The Iliad (best in Greek, but Richmond Lattimore’s translation rules if you’re stuck with English. There is also a new translation by Caroline Alexander, supposedly the first woman’s translation of The Iliad ever published.)

- Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy

- Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth

- Chang-Rae Lee’s The Surrendered

- Jayne Ann Phillips’s Lark & Termite

- Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya’s The Watch (it’s a retelling of Antigone in Afghanistan)

- Herman Wouk’s The Winds of War

- Virgil’s Aeneid (best in Latin, but there are several good translations: Richard Fagles’ is excellent,

- Bobbie Ann Mason’s The Girl in the Blue Beret (I wrote about it here)

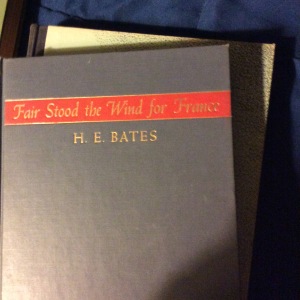

This brilliant novel, published in 1963, is astonishing from the opening sentence. “One autumn in the late nineteen-twenties for no particular reason at all, as it would seem, we began to live in France.” I love the whimsy of that sentence. It describes a life of money, where such decisions can be causally made. And because each sentence is equally glittering and perfect, I could not put this book down. The structure is perfect: events repeat and form a pattern in this inter-generational novel, though in each generation events have a different meaning.

This brilliant novel, published in 1963, is astonishing from the opening sentence. “One autumn in the late nineteen-twenties for no particular reason at all, as it would seem, we began to live in France.” I love the whimsy of that sentence. It describes a life of money, where such decisions can be causally made. And because each sentence is equally glittering and perfect, I could not put this book down. The structure is perfect: events repeat and form a pattern in this inter-generational novel, though in each generation events have a different meaning.

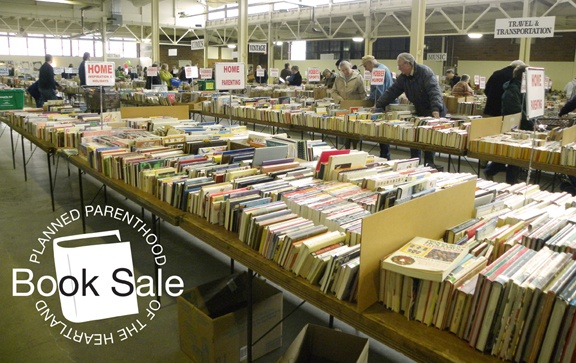

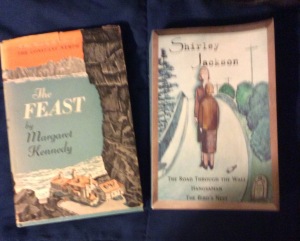

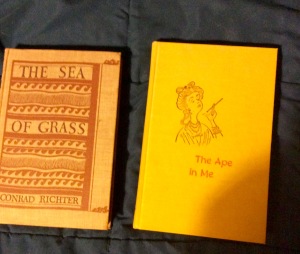

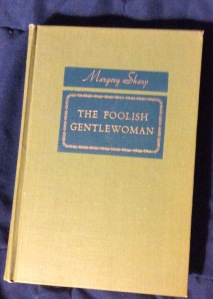

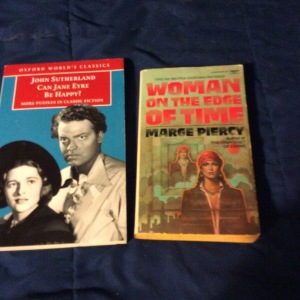

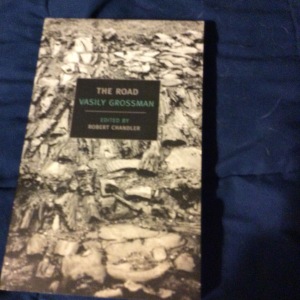

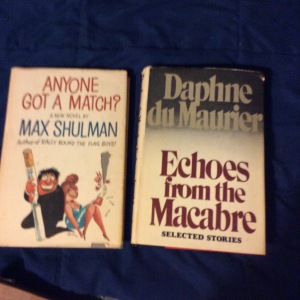

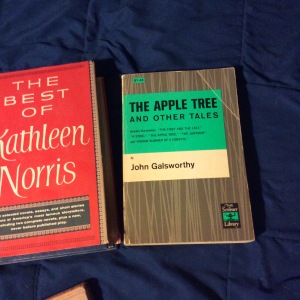

There is a certain kind of detective story I find irresistible. I have always enjoyed Patricia Moyes’s mysteries. Have I read all of these? Maybe. I’ll know when I read them.

There is a certain kind of detective story I find irresistible. I have always enjoyed Patricia Moyes’s mysteries. Have I read all of these? Maybe. I’ll know when I read them. In the contemporary fiction section, I found two books I have long meant to read. Nicole Krauss was nominated for the National Book Award for Great House, and that is an literary award I take seriously, possibly because the prize is judged by writers instead of journalists. (A few years ago the journalist judges of the Pulitzer Prize had a hissy fit and decided not to award the prize for fiction.) Kathryn Davis is a lyrical, original writer, and her novel The Walking Tour is one of my favorites. I am ridiculously behind in reading contemporary literature, and cannot believe I missed The Thin Place.

In the contemporary fiction section, I found two books I have long meant to read. Nicole Krauss was nominated for the National Book Award for Great House, and that is an literary award I take seriously, possibly because the prize is judged by writers instead of journalists. (A few years ago the journalist judges of the Pulitzer Prize had a hissy fit and decided not to award the prize for fiction.) Kathryn Davis is a lyrical, original writer, and her novel The Walking Tour is one of my favorites. I am ridiculously behind in reading contemporary literature, and cannot believe I missed The Thin Place.

Do we need reading gimmicks? Every book website has one. At Goodreads, you can participate in

Do we need reading gimmicks? Every book website has one. At Goodreads, you can participate in