I’ve already done my summer reading: three silly books that would have been better saved for that horsefly-haunted fishing lodge I will find myself in soon.

But they are no less frothy than most of what will be promoted this summer!

FIRST, THE ROMANCE NOVELLA.

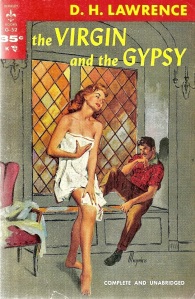

D. H. Lawrence is one of my favorite English writers. I love his poetry, novels, and travel writing. His style can be intense, but I appreciate intensity. Why, why, why did I not get on a train to Nottingham, his birthplace, when I was in England? Well, he didn’t like Nottingham much. And he wasn’t that keen on England.

Is he still in fashion? I have no idea. My obsession began when I saw the movie Women in Love, starring Glenda Jackson, who won the Oscar for Best Actress, Oliver Reed, Alan Bates, and Jennie Linden. And then I was enraptured by the novel Women in Love, though I tried to be cool about it, because my best friend thought it was very funny. It is one of the strangest, loveliest, most seductive books I’ve ever read. The Rainbow, its prequel, is even more stunning. I also like Sons and Lovers, his beautiful coming-of-age novel.

And then there’s The Virgin and the Gipsy.

And then there’s The Virgin and the Gipsy.

Mind you, I enjoyed The Virgin and the Gipsy, but Lawrence’s sexual philosophy can seem ridiculous when concentrated in a novella. He needs a short story or a novel.

It is actually a typical Lawrence story of forbidden sexual attraction between a middle-class woman and a lower-class man. Think Lady Chatterley’s Lover, only sillier. It begins almost like a fairy tale. The rebellious Yvette and her older sister, Lucille, are trapped in the rigid life of a rectory dominated by a grim granny referred to as the Mater. We learn that their mother, Cynthia, left the rector for a penniless man when the girls were children. And their Aunt Cissie sizzles furiously about the house hating both girls, but especially Yvette.

So, naturally, the girls like to get out. One day the wild Yvette is out in a car with Lucille and some other young people, and they almost run down a gipsy cart. The cart finally gets over to the side of the road, but the driver is furious.

Yvette’s heart gave a jump. The man on the cart was a gipsy, one of the black, loose-bodied, handsome sort.

He asks if they would like their fortunes told.

She met his dark eyes for a second, their level search, their insolence, their complete indifference to people like Bob and Leo, and something took fire in her breast. She thought: “he is stronger than I am! He doesn’t care!”

Yvette experiences pure sexual attraction. This is a little overwritten, though.

Yvette has clandestine meetings with the gipsy. Sometimes he drives his cart past their house and she runs out, other times Yvette resists. She is also scandalizes her granny by befriending a couple who are living in sin while they wait for the woman’s divorce.

It’s a little silly. Still, it seemed pure sex when I was an adolescent.

So maybe it’s a Y.A. book?

SECOND, THE COZY MYSTERY THAT’S TOO COZY.

I picked up a couple of mysteries by Patricia Moyes, because they were very nice paperback editions with crisp pages. I THINK I read about them at a blog.

I picked up a couple of mysteries by Patricia Moyes, because they were very nice paperback editions with crisp pages. I THINK I read about them at a blog.

Well, damn, Down Among the Dead Men is just not that good.

Chief Inspector Henry Tibbetts and his wife Emmy go on vacation with friends, Rosemary and Alastair, who have a sailboat. And then they (and we) have to learn everything about sailing.

Alastair looked at him pityingly. “If the jib didn’t have a port and a starboard sheet, how could you come about?” Henry said he had no idea, and watched humbly as Alastair picked up another rope from the deck.

If the jib didn’t…? It’s a lot like Nancy Drew. Everything has to be explained, and over-explained, until you’re ready actually to put your backs into it and heave ho!

Anyhow, they sail with a bunch of friends, including a saucy sexpot of a woman, Ann, whom the other women hate (including me).

And Henry figures out that a friend of theirs who died tragically was actually murdered.

And Ann puts her hands all over him and makes him promise to stop saying he was murdered.

And…

Okay, but not good enough. Maybe this isn’t Moyes’ best?

THIRD, THE SIMENON THAT’S VERY SIMENON-Y.

Of course Simenon is excellent, if you like that kind of thing. The Grand Banks Cafe is a police procedural, straight investigation with no real rounded characters, and lots of re-creation of the crime going on in Maigret’s mind.

Of course Simenon is excellent, if you like that kind of thing. The Grand Banks Cafe is a police procedural, straight investigation with no real rounded characters, and lots of re-creation of the crime going on in Maigret’s mind.

Maigret, a French detective, and his wife go on vacation in a fishing port so he can help clear the name of a teacher friend’s student, Pierre, who was the wireless operator of a ship whose voyage was apparently doomed. (Lots of accidents.) Pierre is accused of murdering the captain after they came ashore. The investigation gets stranger and more bizarre as Maigret discovers that a femme fatale was involved with three of the men on the ship.

Very tight, short, and fast. One of the better Simenons.

And if you want it, it’s yours. I’m giving away the Simenon. Leave a comment if you’d like the book.

We’re pretty much under the radar at Mirabile Dictu. Clickbait wouldn’t work here: there aren’t enough readers. Heavens, I get complaints if I “disrespect” Jane Austen, which I don’t do, but which someone thought I did. I don’t sell ads–it’s too much trouble to be an Amazon associate and add book links to Amazon, on top of all the scribbling I do. Anyway I’m only a one-woman operation and “review”only a couple of books a week. The rest of the time I’m writing about vaguely bookish topics that don’t sell anything except whether I heart (or don’t heart )reveiwers/writers/ bloggers, depending on what I’m saying.

We’re pretty much under the radar at Mirabile Dictu. Clickbait wouldn’t work here: there aren’t enough readers. Heavens, I get complaints if I “disrespect” Jane Austen, which I don’t do, but which someone thought I did. I don’t sell ads–it’s too much trouble to be an Amazon associate and add book links to Amazon, on top of all the scribbling I do. Anyway I’m only a one-woman operation and “review”only a couple of books a week. The rest of the time I’m writing about vaguely bookish topics that don’t sell anything except whether I heart (or don’t heart )reveiwers/writers/ bloggers, depending on what I’m saying.

Allingham explores the ethics of a murder investigation. They track one of the suspects to France, and when they meet up with Joan and Norah there, W. T. says there is no choice bu tto investigate them further. Jerry is upset: he wants his father to leave Norah alone and asks, “What does it matter who killed him?”

Allingham explores the ethics of a murder investigation. They track one of the suspects to France, and when they meet up with Joan and Norah there, W. T. says there is no choice bu tto investigate them further. Jerry is upset: he wants his father to leave Norah alone and asks, “What does it matter who killed him?”

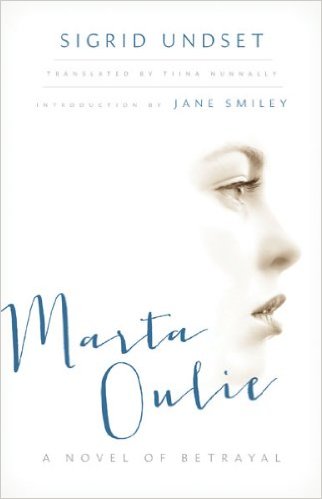

Sigrid Undset, who won the Nobel Prize in 1928, is best known for her brilliant historical trilogy, Kristin Lavrandsatter, and The Master of Hestviken tetralogy. I recently reread Kristin Lavransdatter, one of my favorite books of all time. (I wrote about it

Sigrid Undset, who won the Nobel Prize in 1928, is best known for her brilliant historical trilogy, Kristin Lavrandsatter, and The Master of Hestviken tetralogy. I recently reread Kristin Lavransdatter, one of my favorite books of all time. (I wrote about it  In both stories, a marriage begins happily, but becomes boring to the women. Both heroines (Marta and Tolstoy’s Masha) tire of their constricted lives. Marta, a teacher, is restless. She was very much in love with Otto when they married, but after her second child she needed something else.

In both stories, a marriage begins happily, but becomes boring to the women. Both heroines (Marta and Tolstoy’s Masha) tire of their constricted lives. Marta, a teacher, is restless. She was very much in love with Otto when they married, but after her second child she needed something else. I know, I know: you don’t expect me to wrtie about Goodreads. I trashed it at this blog once. But I am now a full-fledged gladiator of the consumer culture. “We who are about to read salute you!”

I know, I know: you don’t expect me to wrtie about Goodreads. I trashed it at this blog once. But I am now a full-fledged gladiator of the consumer culture. “We who are about to read salute you!” I gave 4 stars to Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils.

I gave 4 stars to Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils. The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis, John Banville (Introduction)

The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis, John Banville (Introduction)