Elizabeth Jane Howard (1923-2014), best known for the Cazalet Chronicle, a five-volume literary family saga, seems to be having a revival.

In January Hilary Mantel wrote in The Guardian that Howard’s books are underrated. She especially likes The Long View.

But the real reason the books are underestimated – let’s be blunt – is that they are by a woman. Until very recently there was a category of books “by women, for women”. This category was unofficial, because indefensible. Alongside genre products with little chance of survival, it included works written with great skill but in a minor key, novels that dealt with private, not public, life. Such novels seldom try to startle or provoke the reader; on the contrary, though the narrative may unfold ingeniously, every art is employed to make the reader at ease within it.

Fortunately, Open Road Media has recently reissued all of Howard’s books as e-books. And several bloggers have reviewed them, including The Bookbinder’s Daughter, The Homebody, and Dovegreyreader.

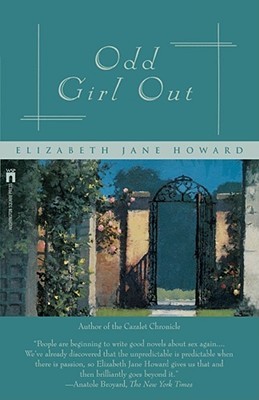

I discovered Howard in the ’90s and started with the Cazalet Chronicle. Over the years, I have tracked down the rest of her books and loved them. In the mood for some fast summer reading, I rummaged through my bookcase and recently picked Howard’s Odd Girl Out (1972).

Odd Girl Out is, as you might guess, the story of a triangle. It is deftly written, bold, and curiously modern, though it is not Howard’s best book. It is, however, a compelling summer read, with the frankness and eroticism of so many women’s novels of the late twentieth century.

Odd Girl Out is, as you might guess, the story of a triangle. It is deftly written, bold, and curiously modern, though it is not Howard’s best book. It is, however, a compelling summer read, with the frankness and eroticism of so many women’s novels of the late twentieth century.

It begins with an idyllic scene: Anne and Edmund Cornhill, a sexy married couple, are eating breakfast in bed in their lovely country house. They are discussing the imminent visit of Arabella, the daughter of Clara, Edmund’s stepmother during a very brief marriage to his father.

Anne is very easygoing about the visit.

“Of course I don’t mind, my darling. Of course I don’t.” She wore the top half of his pajamas and was putting cherry jam on a piece of toast. She thought for a moment, and then added, “It will be lovely for me to have someone to talk to while you’re in London.”

This happy couple, who have fabulous sex every night, do not anticipate disruption. Edmund works in London as an estate agent; Anne is a housewife who enjoys gardening, cooking, and Elizabeth Taylor’s novels.

Howard is a master of third-person point-of-view narrative and, in short segments, shows us perspectives of several characters. Before we meet Arabella, we are introduced to her rich mother Clara and the latest in a string of husbands (this one is a prince), who are planning a Caribbean cruise and plotting to marry the problematic Arabella off to a rich old man; and Janet, a penniless housewife and mother of two whose actor husband, Harry, whom she no longer loves, has deserted her for another woman (Arabella).

We meet Arabella while she is having an abortion, lying on a “high, hard, humiliatingly uncomfortable table.” Afterwards, she spends the day in pain sitting on benches at the zoo and visiting her favorite gorilla: she has no home, because she has walked out on Janet’s husband, Harry, and is waiting to take the evening train to Henley, because the Cornhills are the only people left for her to visit. Ann and Edmund somehow mistake her for a child: she has very good manners and demands very little.

But, yes, she wedges her way into their life. She has been neglected by her rich mother and feels she has never been loved. She adores the atmosphere of the Cornhills’ home and and wants to be a part of it. Edmund seduces her, but she has known it would happen and has bought a new outfit for the occasion, and afterwards she asks him happily if he loves her more and says that’s why she slept with him. Then, while he is away in Greece for weeks on business, she seduces Ann. Of course Anne and Edmund have no idea Arabella is so promiscuous.

Arabella is the link between every character in the novel, and she wreaks havoc. She is not an entirely unsympathetic character: she is simply so rich and has been brought up so badly she doesn’t know how to have relationships. She stays with various people for short periods of time and then she leaves. But the Cornhills are a real couple, and she wants what they have.

Howard can see all points of view. During their idyllic affair, Arabella and Ann have long conversations about whether women are nicer than men. (The bisexual Arabella favors women.) Edmund is the least sympathetic character, self-centered and insensitive. But Arabella’s unwitting effect on Janet, the wife of Harry, her last boyfriend, turns out to be so dire that we can’t overlook it.

Miss Crane’s hubris during a day of social unrest and rioting–she insists on returning home from the village where she has spent the night at the house of an Indian teacher and his family, though the phone lines have been cut and the police advise her there has been violence–results in the murder of the Indian teacher who insists on accompanying her, when she simply can’t make herself put her foot on the accelerator and drive through the crowd. After his death, Miss Crane’s entire view of every good deed she thought she had done in India is dust. She commits suttee, as if she were the wife of the teacher.

Miss Crane’s hubris during a day of social unrest and rioting–she insists on returning home from the village where she has spent the night at the house of an Indian teacher and his family, though the phone lines have been cut and the police advise her there has been violence–results in the murder of the Indian teacher who insists on accompanying her, when she simply can’t make herself put her foot on the accelerator and drive through the crowd. After his death, Miss Crane’s entire view of every good deed she thought she had done in India is dust. She commits suttee, as if she were the wife of the teacher.

These elegantly-written “middlebrow” novels are the kind of books reissued by Virago and Persephone. Plot does not define them so much as intelligence, though the plots are absorbing. In Listening to Billie, the heroine, Eliza, a poet, the daughter of a selfish, eccentric nonfiction writer, is a Billie Holiday fan. She marries her boyfriend, Evan, a professor, after she gets pregnant. Evan turns out to be a very unhappy homosexual. He stalks a student, the oblivious Reed Ashford, the most beautiful boy he has ever seen, and when he realizes he can never have him, he commits suicide. Eliza does not allow her life to be ruined: she moves to San Francisco and establishes a fulfilling life with her daughter. She works part- time as a secretary and begins to sell her poetry to magazines like the Atlantic. She is a very kind character and a good friend: I would love to know her. Oddly, she meets Reed Ashford in San Francisco, and they are instantly attracted, two beautiful blondes. They have an affair, which is perfect while it lasts.

These elegantly-written “middlebrow” novels are the kind of books reissued by Virago and Persephone. Plot does not define them so much as intelligence, though the plots are absorbing. In Listening to Billie, the heroine, Eliza, a poet, the daughter of a selfish, eccentric nonfiction writer, is a Billie Holiday fan. She marries her boyfriend, Evan, a professor, after she gets pregnant. Evan turns out to be a very unhappy homosexual. He stalks a student, the oblivious Reed Ashford, the most beautiful boy he has ever seen, and when he realizes he can never have him, he commits suicide. Eliza does not allow her life to be ruined: she moves to San Francisco and establishes a fulfilling life with her daughter. She works part- time as a secretary and begins to sell her poetry to magazines like the Atlantic. She is a very kind character and a good friend: I would love to know her. Oddly, she meets Reed Ashford in San Francisco, and they are instantly attracted, two beautiful blondes. They have an affair, which is perfect while it lasts.