It is National Poetry Month, and I am musing on bad poetry.

In Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry), Horace’s charming guide to classical poetry, he traces the history of the genre and explains the elements of writing good poetry. He also fulminates against inept poets who lack natural talent or knowledge of the art.

The difference between sports fans and poetry fans, he explains, is that sports fans know that they are unlikely to become professional athletes, while every poetry reader believes he can be a great poet. Although Horace expresses this sentiment elegantly in Latin hexameters, it doesn’t quite come across in English. Here’s my rough prose translation.

If a man does not know how to play, he refrains from military sports on the Campus Martius,

And if he is unskilled at sports, at ball, the discus, or the hoop, he doesn’t participate,

lest the crowd of spectators laugh at him.

And yet a man who knows nothing dares to fashion verses!

I did laugh. It is so true: everybody’s a poet/novelist/critic!

I used to belong to a poetry group. It was fun and therapeutic. Only one of us, and it was not I, had talent. Some thought they were as good as our prima, who’d published a few poems in little magazines, but honestly they (we) had a long way to go. And there was not much grumbling, because our prima was likable, as is so often the case.

What does one do at a poetry group meeting? Well, we ate homemade cake, gently critiqued each other’s poems, and sometimes did poetry-writing exercises. (N.B. There are good poetry exercises on Tuesdays at Poets & Writers.) We also attended the readings of the few brave who read on Open Mic nights at the coffeehouse. The great thing about Open Mic nights is that nobody can tell if your poetry is good or bad if you’re a good actor !

Part of what we like is playing the role of poet: Horace hated that! He thought it was absurd to pretend to be a poet by neglecting one’s appearance, not bathing, and growing a beard. Obviously he didn’t know female poets, who spend a lot of time on hair and clothes!

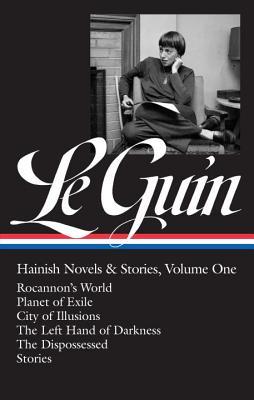

Anyway, here is a poem about poems by Octavio Paz, translated by Eliot Weinberger. (I hope Horace would approve.)

Proem

At times poetry is the vertigo of bodies and the vertigo of speech and the vertigo of death;

the walk with eyes closed along the edge of the cliff, and the verbena in submarine gardens;

the laughter that sets on fire the rules and the holy commandments;

the descent of parachuting words onto the sands of the page;

the despair that boards a paper boat and crosses,

for forty nights and forty days, the night-sorrow sea and the day-sorrow desert;

the idolatry of the self and the desecration of the self and the dissipation of the self;

the beheading of epithets, the burial of mirrors; the recollection of pronouns freshly cut in the garden of Epicurus, and the garden of Netzahualcoyotl;

the flute solo on the terrace of memory and the dance of flames in the cave of thought;

the migrations of millions of verbs, wings and claws, seeds and hands;

the nouns, bony and full of roots, planted on the waves of language;

the love unseen and the love unheard and the love unsaid: the love in love.

Syllables seeds.