I recently subscribed to The New York Review of Books and The Times Literary Supplement (TLS). Mind you, I didn’t want to. I wanted to buy a new set of dishes at Target.

But it seems I should “invest” in such publications if I want to “hold the line.”

With a few exceptions, mainstream book reviews seem to be going down. Critics say everybody’s a critic: well, they still need to do their job. Formerly reliable book pages (The New York Times, The Washington Post, etc.) are occasionally still brilliant, but have acquired a new nervous tone, like a homecoming queen smiling too hard as she coaxes votes from the hoi polloi (οἱ πολλοί). As newspapers fold, editors try to attract a new audience: they waste space on romances, Stephen King, and “pastel lit” (otherwise known as chick lit”). God help me, Emma Straub’s Modern Lovers is the fluffiest of beach books, and I read it because Michiko Kakutani reviewed it, and The Washington Post actually reviewed Ann Patty’s error-riddled Living With a Dead Language: My Romance with Latin, an inconsequential, poorly-written memoir of her auditing of Latin classes, consultation of “laminated SparkNotes,” and shallow observations on Roman literature. My husband and I, who are both Latinists, refer to Patty, a former New York editor who discovered V. C. Andrews, as “the new Lucia.”

And to think New York editors blame Amazon for their problems!

All right, so I can breathe again. The TLS , The New York Review of Books, and The New Yorker are holding the line.

In the “N.B.” column in the TLS (June 15, 2016), J. C. writes about George Gissing.

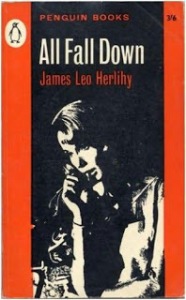

Some weeks ago, we made a modest suggestion to the editors at Penguin Classics: to publish George Gissing’s disguised memoir The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903) in a single volume with Morley Roberts’s memoir of Gissing, The Private Life of Henry Maitland. Roberts’s book, published in 1912, nine years after Gissing’s death, is itself an act of disguise. It uses fictitious names for well-known personages – G. H. Rivers for H. G. Wells; Schmidt for Gissing’s friend Eduard Bertz – and for books: for Paternoster Row, read New Grub Street; for The Unchosen, The Odd Women. Distracting at first, this habit eventually has a certain charm; Roberts’s biography is as much a work of the imagination as Gissing’s autobiography. Hence our proposal to Penguin to compensate for its past neglect of Gissing. So far we haven’t heard back.

Oh, what a good idea! I could do with a Penguin set of Gissing. I recently started Gissing’s brilliant novel, Born in Exile, which novelist and critic D. J. Taylor has said is his favorite book. I was only able to find a used Everyman paperback, and the print is too small. I’ve had to turn to the e-book.

And The New York Review of Books (June 23, 2016) is also doing its job. Daniel Mendelsohn’s brilliant article, “How Greek Drama Saved the City,” examines the difference between theater in ancient Greece and the modern U.S. Here is an excerpt from Mendelsohn’s essay:

At the climax of Aristophanes’ comedy Frogs, a tartly affectionate parody of Greek tragedy that premiered in 405 BCE, Dionysus, the god of wine and theater, is forced to judge a literary contest between two dead playwrights. Earlier in the play, the god had descended to the Underworld in order to retrieve his favorite tragedian, Euripides, who’d died the previous year; without him, Dionysus grumpily asserts, the theatrical scene has grown rather dreary. But once he arrives in the land of the dead, he finds himself thrust into a violent literary quarrel. At the table of Pluto, god of the dead, the newcomer Euripides has claimed the seat of “Best Tragic Poet”—a place long held by the revered Aeschylus, author of the Oresteia, who’s been dead for fifty years.

A series of competitions ensues, during which excerpts of the two poets’ works are rather fancifully compared and evaluated—scenes replete with the kind of in-jokes still beloved of theater aficionados. (At one point, lines from various plays by the occasionally bombastic Aeschylus are “weighed” against verses by the occasionally glib Euripides: Aeschylus wins, because his diction is “heavier.”) None of these contests is decisive, however, and so Dionysus establishes a final criterion for the title “Best Tragic Poet”: the winner, he asserts, must be the one who offers to the city the most useful advice—the one whose work can “save the city.”

Today, the idea that a work written for the theater could “save” a nation—for this was what Aristophanes’ word polis, “city,” really meant; Athens, for the Athenians, was their country—seems odd, even as a joke. For us, popular theater and politics are two distinct realms. In the contemporary theatrical landscape, overtly political dramas that seize the public’s imagination (Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, say, with its thinly veiled parable about McCarthyism, or Tony Kushner’s AIDS epic Angels in America) tend to be the exception rather than the rule; and even the most trenchant of such works are hardly expected to have an effect on national policy or politics (let alone to “save the country”). Such expectations are dimmer still when it comes to other kinds of drama. The lessons that A Streetcar Named Desire has to teach about beauty and vulnerability and madness are lessons we absorb as private people, not as voters.

By the way, last fall I wrote a blog entry on “Filthy Jokes in Aristophanes.” (It is NOT intellectual! That’s why I need the NYRB.)

Do you have any observations on good, bad, or indifferent book reviews? Are they “going down?” Favorite publications? Favorite blogs? I know I’ve asked this before. I need to add some new American blogs to my blogroll! Some of my favorites have quit.

Barbara Trapido’s Temples of Delight (1990), shortlisted for the Sunday Express Book of the Year Award, is one of the most charming novels I’ve ever read. Think Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, with a touch of Nancy Mitford and Nora Ephron. Trapido’s sharp, witty novel centers on Alice Pilling, a bright young woman who eventually studies classics at Oxford. But the main event of her life is her teenage friendship with Jem McCrail, who shows up one day in Miss Aldridge’s Silent Reading Hour at school. Jem’s unusual stories about her eccentric family, her ability to recite poetry, and her habit of scribbling her own very good novels in notebooks, make her a star who inspires love and hate equally among the students.

Barbara Trapido’s Temples of Delight (1990), shortlisted for the Sunday Express Book of the Year Award, is one of the most charming novels I’ve ever read. Think Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, with a touch of Nancy Mitford and Nora Ephron. Trapido’s sharp, witty novel centers on Alice Pilling, a bright young woman who eventually studies classics at Oxford. But the main event of her life is her teenage friendship with Jem McCrail, who shows up one day in Miss Aldridge’s Silent Reading Hour at school. Jem’s unusual stories about her eccentric family, her ability to recite poetry, and her habit of scribbling her own very good novels in notebooks, make her a star who inspires love and hate equally among the students.