Last year the Library of America published two volumes of women’s noir classics, Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s and Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1950s. The writers included in these two volumes–Vera Caspary, Helen Eustis, Dorothy B. Hughes, Elisabeth Sanxay, Charlotte Armstrong, Patricia Highsmith, Margaret Millar, and Dolores Hitchens–were pioneers of domestic suspense.

Last year the Library of America published two volumes of women’s noir classics, Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s and Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1950s. The writers included in these two volumes–Vera Caspary, Helen Eustis, Dorothy B. Hughes, Elisabeth Sanxay, Charlotte Armstrong, Patricia Highsmith, Margaret Millar, and Dolores Hitchens–were pioneers of domestic suspense.

According to editor Sarah Weinman’s introduction at the Library of America Women in Crime website, women often set their books against a domestic background.

Women’s magazines are of particular interest in the story of domestic suspense, because of their audience:Young and middle-aged women, single and married were seeking respite from their ennui and alienation. The appearance of domestic suspense fiction poked holes in the “happy homemaker” ideal put forward by the more positive, beauty-and fashion-oriented articles.

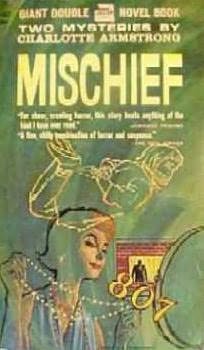

After enjoying the 1940s volume last fall, I have finally embarked on the 1950s. Charlotte Armstrong’s clever, gritty suspense novel, Mischief (1950), is terrifying. It reminds us that, even in the flourishing economy of the 1950s, there was a threat to the security of domestic life.

After enjoying the 1940s volume last fall, I have finally embarked on the 1950s. Charlotte Armstrong’s clever, gritty suspense novel, Mischief (1950), is terrifying. It reminds us that, even in the flourishing economy of the 1950s, there was a threat to the security of domestic life.

In Mischief, the middle-class Jones family is as secure as they can be. When Peter O. Jones, the busy editor and publisher of the Brennerton Star-Gazette, goes to a convention in New York, he takes his wife Ruth and daughter Bunny along. They plan to spend a few days seeing New York after the convention. They stay at the Majestic Hotel in midtown Manhattan.

But there’s a glitch: Peter’s sister Betty calls to say she can’t babysit for Bunny while he and Ruth attend the dinner. Peter has to make a speech, and Ruth wants to hear it. And so the very nice elevator man, Eddie, who has worked at the hotel for 15 years, says his niece, Nell, can babysit. She is very quiet. Ruth notices there’s something slightly off about her demure manner. But they’ll be gone only a few hours.

From the very first page, Ruth comes across as a strong, intelligent character. Peter is kind, but he is absorbed in work, so she is the one who must protect the family from domestic problems. On the first page she muses about hotels.

What a formula, she thought, is a hotel room. Everything one needs. And every detail pursued with such heavy-handed comfort, such gloomy good taste, it becomes a formula for luxury. The twin beds, severely clean, austerely spread. The lamp and the telephone between. Dresser, dressing table. Desk and desk chair (if the human unit needs to take his pen in hand). Bank of windows, on a court, with the big steam radiator across below them, metal topped. Curtains in hotel-ecru. Draperies in hotel-brocade. Easy chair in hotel-maroon. The standing lamp. The standing ash tray, theat hideous useful thing. The vast empty closet. And the bath. The tiles. The big towels. The small soap. The very hot water.

One of the fascinating things about Armstrong’s brilliant plotting is that no detail is wasted. Every item in the paragraph above is crucial to the plot.This is a short book, but no word is wasted. What looks like domestic life can’t be domestic in a hotel.

One of the fascinating things about Armstrong’s brilliant plotting is that no detail is wasted. Every item in the paragraph above is crucial to the plot.This is a short book, but no word is wasted. What looks like domestic life can’t be domestic in a hotel.

Ruth can’t get over the nagging feeling she shouldn’t leave Bunny with Nell. She tries to overcome it with logic.

And Nell doesn’t do anything untoward at first. After reading a story to Bunny in a monotone (Bunny is puzzled: why is it so much more interesting when Mommy reads it?), Nell says Good night and leaves the door to the adjoining room slightly open as Ruth had requested. Then she embarks on mischief. Nell makes a lot of expensive crank phone calls. (The switchboard operator notices and wonders what’s going on.) Then she goes through Ruth and Peter’s things. She tries on Ruth’s clothes and jewelry, walks around in her mules, and spills the perfume and powder on the dressing table. Uncle Eddie pops in on his break and nervously tries to persuade her to put everything back. The thing is, Nell goes several steps farther than any normal snoopy babysitter would.

Another resident of the hotel, Jed, has quarreled with girlfriend Lyn on his last night in New York. So he smokes a cigarette outside, and makes eye contact with Nell as she looks out the window. (Armstrong calls the hotel “a fish bowl.”) He goes up to the room to flirt with her (or score), but soon realizes Nell is a nut: when he tries to leave, she threatens him and he wants to calm her down. When her uncle Eddie comes back, she pushes Jed into the bathroom. And then things get more and more berserk.

Marilyn in the film, “Don’t Bother to Knock.”

I shall say no more because the book is very plot-oriented. And, the way, it was filmed in 1952 as Don’t Bother to Knock and starred Marilyn Monroe. (I haven’t seen it.)

Armstrong was a very prolific writer: a playwright, a mystery writer, a suspense novelist. She even published three poems in The New Yorker.

I used to see her books around but since I wasn’t a big fan of mysteries or suspense novels I never bothered with them. Now I shall.

The other novels in Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1950s are Patricia Highsmith’s The Blunderer, Dorlores Hitchens’s Fool’s Gold, and Margaret Millar’s Beast in View. Perfect summer reading!

Then one day she realizes his girlfriend is Victorine. Elisa is crushed but determined to stay level-headed. She pretends she doesn’t know; then she becomes his confidant. And she is hurt very much.

Then one day she realizes his girlfriend is Victorine. Elisa is crushed but determined to stay level-headed. She pretends she doesn’t know; then she becomes his confidant. And she is hurt very much. I chortled over the quotation below from Compton Mackenzie’s comic novel, Extraordinary Women.

I chortled over the quotation below from Compton Mackenzie’s comic novel, Extraordinary Women.