How does home define us? Is it a house, or an atmosphere?

Proust nibbled a madeleine, but I recalled my Edenic girlhood when I visited my mother’s house. The tree-lined neighborhood didn’t change much over the years, and the back yard was lush with two apple trees, a weeping willow, a pear tree, and an evergreen. And though I did not read in trees–I was not a character in a Louisa May Alcott novel–I spent hours reading in a lawn chair outside. I remembered home, the trees, and the books simultaneously.

Since my mother’s death a few years ago, I have visited my hometown less often. So was home my mother? Or was it the house as well, now sold? Home means something different to me now: home is the present, rather than the present and the past. Today, musing about the meaning of home, I have complied a list of 10 Novels about Houses. Not all are homey, but Godden’s especially applies. And do tell me your favorites!

1 A Fugue in Time, or Take Three Tenses by Rumer Godden. This enchanting novel revolves around a house, 99 Wiltshire Place. When the 99-year lease is up, Rolls Dane, the ancient tenant, is enraged that the lease cannot be renewed. And so he sits and contemplates family history. The house, with a plane tree in the yard, and the Dane family are inextricably intertwined. And time overlaps: the present, past, and future happen at once. In a single paragraph, Godden switches from the perspective of a character in the 1940s to that of a character in the 19th century. And, finally, the visit of an American niece changes the house’s history. (You can read my post here.)

1 A Fugue in Time, or Take Three Tenses by Rumer Godden. This enchanting novel revolves around a house, 99 Wiltshire Place. When the 99-year lease is up, Rolls Dane, the ancient tenant, is enraged that the lease cannot be renewed. And so he sits and contemplates family history. The house, with a plane tree in the yard, and the Dane family are inextricably intertwined. And time overlaps: the present, past, and future happen at once. In a single paragraph, Godden switches from the perspective of a character in the 1940s to that of a character in the 19th century. And, finally, the visit of an American niece changes the house’s history. (You can read my post here.)

2 We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. In 2015 I wrote at this blog: “Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in a Castle is a clas-SICK! It is a horror take on Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle. Smith’s novel is narrated by the benign, humorous Cassandra Mortmain, an aspiring writer who lives in a dilapidated castle with her eccentric family. The narrator of Jackson’s novel, Mary Catherine Blackwood, lives only with her sister in the large country house because the rest of her family is dead from arsenic poisoning…. Beautifully written, funny, horrible, and perfect.”

2 We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. In 2015 I wrote at this blog: “Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in a Castle is a clas-SICK! It is a horror take on Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle. Smith’s novel is narrated by the benign, humorous Cassandra Mortmain, an aspiring writer who lives in a dilapidated castle with her eccentric family. The narrator of Jackson’s novel, Mary Catherine Blackwood, lives only with her sister in the large country house because the rest of her family is dead from arsenic poisoning…. Beautifully written, funny, horrible, and perfect.”

3 I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. I wrote in my book journal in 2012: I try to reread I Capture the Castle once a year. Usually I read it on Midsummer Night’s Eve, because there is a very funny scene in which Cassandra celebrates with a bonfire and some witchery. But this year I’m reading it two days after the Fall Equinox–do you think that counts?

3 I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. I wrote in my book journal in 2012: I try to reread I Capture the Castle once a year. Usually I read it on Midsummer Night’s Eve, because there is a very funny scene in which Cassandra celebrates with a bonfire and some witchery. But this year I’m reading it two days after the Fall Equinox–do you think that counts?

The narrator, Cassandra Mortmain, a 17-year-old aspiring writer, “captures” her life in a journal: she and her family live in a mouldering castle, which her father, James, bought on the proceeds of a Joycean novel he wrote. But he has inexplicably stopped writing, sits in the gatehouse all day reading mysteries, and thus the Mortmains have no income to speak of. In a very funny scene early in the book, the librarian, Miss Marcie, tries to help them figure out their earning power, and they are an unpromising lot: Cassandra’s stepmother, Topaz, is a former artist’s model who loves to commune with nature in the nude; Cassandra’s beautiful 21-year-old sister, Rose, wants to marry but knows no men; and their younger brother Thomas is normal but still at school. Only their servant, Stephen, has real earning power: he can do manual labor.

Fortunately their interactions with some new American neighbors provide both free food and romance.

4 The Past by Tessa Hadley. Every sentence of this novel is exquisitely crafted, and every character brilliantly alive. The book has a tripartite structure: “The Present,” “The Past,” and “The Present.” In the first and last sections, called “The Present,” four adult siblings chat and bicker during a three-week vacation together in the dilapidated, moldering rectory where their mother grew up and their grandparents lived for decades. They must decide whether to keep or sell this summer cottage. The luminous second section holds it together and elucidates their entwined yet separate views of the past.

4 The Past by Tessa Hadley. Every sentence of this novel is exquisitely crafted, and every character brilliantly alive. The book has a tripartite structure: “The Present,” “The Past,” and “The Present.” In the first and last sections, called “The Present,” four adult siblings chat and bicker during a three-week vacation together in the dilapidated, moldering rectory where their mother grew up and their grandparents lived for decades. They must decide whether to keep or sell this summer cottage. The luminous second section holds it together and elucidates their entwined yet separate views of the past.

From the beginning, the siblings squabble about what the past means. Alice holds forth “in one of her diatribes against modern life” that modern objects are not beautiful and have no meaning. Roland is “wary of [her] evaluative judgements,” while Harriet dismisses her romanticism. Fran also gangs up against her.

You can read the entire post here.

5 The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. This lush, poetic masterpiece is laced with magic realism, reminiscent of the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Allende narrates the story of the rise and fall of three generations of the Trueba family in a politically unstable country in South America. I am especially fond of the character Clara, the psychic matriarch who opens their enormous house in the city to eccentrics and adds on rooms and staircases that go nowhere; her daughter, Blanca, a potter who teaches Mongoloids; and her radical granddaughter, Alba, who feeds the homeless and hides refugees in the house after a fascist coup in the city.

5 The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. This lush, poetic masterpiece is laced with magic realism, reminiscent of the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Allende narrates the story of the rise and fall of three generations of the Trueba family in a politically unstable country in South America. I am especially fond of the character Clara, the psychic matriarch who opens their enormous house in the city to eccentrics and adds on rooms and staircases that go nowhere; her daughter, Blanca, a potter who teaches Mongoloids; and her radical granddaughter, Alba, who feeds the homeless and hides refugees in the house after a fascist coup in the city.

6 Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh. The first time I read it, I was teaching at a lovely snob school, and so steeped in classics that Brideshead did not measure up. When I reread it in 2005, I admired the exquisite style and the witty dialogue.

6 Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh. The first time I read it, I was teaching at a lovely snob school, and so steeped in classics that Brideshead did not measure up. When I reread it in 2005, I admired the exquisite style and the witty dialogue.

In Waugh’s great Catholic novel, the narrator Charles Ryder remembers a romantic pre-war past. At Oxford he was befriended by the Catholic aristocrat Sebastian Flyte, and fell in love almost as much with the Flyte’s gorgeous house, Brideshead, as he did later with Sebastian’s sister Julia, whom Charles later married. The novel begins the 1940s when he is an army captain. His company believes it will be dispatched to the Middle East, but, ironically, when they get off the train, the destination turns out to be Brideshead.

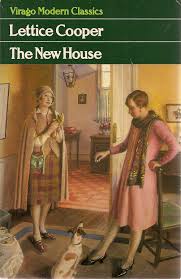

7 The New House by Lettice Cooper. Is it cheating to name a book I barely remember? This was one of my favorite Viragos long ago, and was reissued more recently by Persephone. It is the story of a day in the life of a family as they move from a big beautiful house with a garden to a house overlooking a housing estate. I don’t remember more, but I loved it.

7 The New House by Lettice Cooper. Is it cheating to name a book I barely remember? This was one of my favorite Viragos long ago, and was reissued more recently by Persephone. It is the story of a day in the life of a family as they move from a big beautiful house with a garden to a house overlooking a housing estate. I don’t remember more, but I loved it.

8. The House of the Seven Gables by Nathanael Hawthorne. I haven’t read this one in years, either. A puritanical classic, the story of the Pyncheon family, who live for generations in a gloomy house cursed by a dead man. How can they get rid of the curse?

8. The House of the Seven Gables by Nathanael Hawthorne. I haven’t read this one in years, either. A puritanical classic, the story of the Pyncheon family, who live for generations in a gloomy house cursed by a dead man. How can they get rid of the curse?

9. Slade House by David Mitchell. In this literary horror novel, Mitchell skillfully manipulates the tropes of horror and fantasy. Imagine E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle fused with Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House.

9. Slade House by David Mitchell. In this literary horror novel, Mitchell skillfully manipulates the tropes of horror and fantasy. Imagine E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle fused with Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House.

In this genre-busting page-turner, a supernatural brother and sister prey on the dearest fantasies of gifted human beings after luring them into Slade House. In the opening chapter, the narrator, Nathan, who is autistic with a touch of OCD, and his musician mother have been invited to a concert at Slade House. The problem is they cannot find the house on Slade Alley. Finally, they discover “a small black iron door, set into the brick wall.” It is so small they have to stoop. And then they are in a fantasy garden. Nathan discovers paintings of people with no eyes, and when he finds the painting of himself, we know he’s in a trap.The novel consists of five linked stories between 1979 and 2015, each with a different narrator who is lured into Slade House.

10. Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. The first sentence is unforgettable. “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” Can the unnamed narrator live up to her husband’s first wife, Rebecca when she moves into his forbidding mansion, Manderley? A classic.

10. Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. The first sentence is unforgettable. “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” Can the unnamed narrator live up to her husband’s first wife, Rebecca when she moves into his forbidding mansion, Manderley? A classic.

I am rereading He Knew He Was Right, my favorite novel by Trollope. Is this his masterpiece? Well, I am fond of most of his books, but I do think this is one of the greatest Victorian novels.

I am rereading He Knew He Was Right, my favorite novel by Trollope. Is this his masterpiece? Well, I am fond of most of his books, but I do think this is one of the greatest Victorian novels. This is my fourth reading, but knowing the outcome makes no difference to the pleasure.

This is my fourth reading, but knowing the outcome makes no difference to the pleasure.