Jane Fonda as Lillian Hellman in “Julia” can write anywhere, but this beach house looks nice…. And I think I need a cigarette.

Blogging can be boring. Same-o, same-o. Like a journalist, I can bang out a 700-word post anywhere: at Starbucks, in a bubble bath, or the wilds of the Wisconsin woods.

I often do.

There was the daily diary. Deleted it. There was Frisbee: A Book Journal (still twirling in cyberspace) and Mirabile Dictu since the end of 2012.

Does anyone really want to read about my daily reading?

More important, do I want to write about it?

Is blogging performance art?

And where are the new book blogs? I swear, every blogroll features the same blogs. Are we all in some eerie network? Trapped in cyberspace? And, if so, how did that happen?

And, as a break from these difficult questions, I am banging out a “postette” on The Balzac Problem instead of a longish book post.

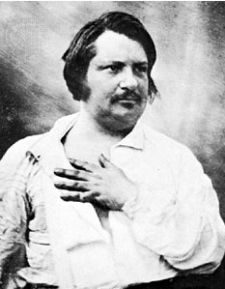

It was going to be the Year of Balzac. Actually, I said it might be. His entertaining novels center on the mesmerizing schemes and unpredictable exploits of misers, courtesans, politicians, journalists, spinsters, coquettes, and con men. His psychological analyses are penetrating and incisive.

In his 95-volume magnum opus, La Comédie humaine, he manically attempted to portray every type of human being and chart every niche of society.

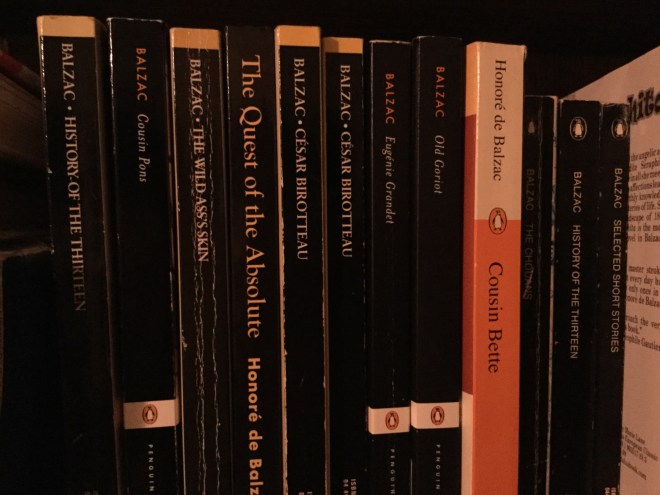

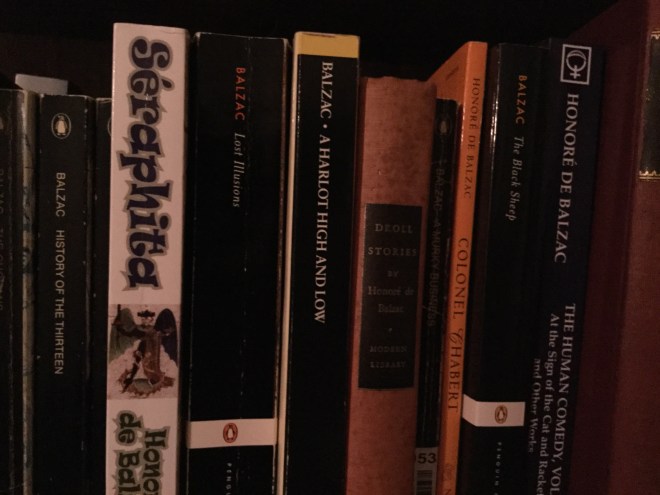

I love Balzac. My favorites are Cousin Bette, Lost Illusions, Pere Goriot, Modeste Mignon, and A Harlot High and Low.

But now I’m leaving behind the Penguin classics and have reached the no-man’s-land of what I call DEEP Balzac. (It’s a little like Deep Throat in All the President’s Men.) I am perusing the lesser-known books, the ones translated by Clara Bell and Ellen Marriage in the late nineteenth-century.

And when a Victorian translator scribbles too fast and clumsily for quick money (they were paid little), you get to know Balzac’s formulas and tricks almost too well. There’s the phrenology and physiology, which so many 19th-century writers took so seriously; the endless exposition (When WILL he start the story?); then the frenetic unrolling of the plot to make up for lost time; and the blunt narration when he tires of constructing the story.

It’s Balzac’s world.

And. much as I wanted to read all 95 novels and stories, I have no desire to write about the entire Human Comedy. I am behind: In December I read The Black Sheep (available in Penguin) and A Daughter of Eve (free at Project Gutenberg), and though both novels are thoroughly enjoyable, they are uneven, with abrupt transitions. I suggest you read and enjoy these two without thinking too hard.

And. much as I wanted to read all 95 novels and stories, I have no desire to write about the entire Human Comedy. I am behind: In December I read The Black Sheep (available in Penguin) and A Daughter of Eve (free at Project Gutenberg), and though both novels are thoroughly enjoyable, they are uneven, with abrupt transitions. I suggest you read and enjoy these two without thinking too hard.

QUICK SYNOPSES

In The Black Sheep, Balzac creates an Oedipal triangle consisting of a mother and two sons. At the apex is Philippe, a gambler/thief/murderer/spendthrift, the favorite son of his widowed mother, Agathe. Her less beloved son, Joseph, is a successful artist who financially supports his mother when, on so many occasions, she is bankrupted by Phillippe. She underrates his success.

But how can Joseph protect her from Phillipe?

Early on, we learn that the generous aunt who shares their flat gambles on a small scale: she buys a lottery ticket with the same number every day for years and years. So perhaps the gambling is in the family. Phillippe, too, is addicted to gambling. He steals from his aunt and horrifyingly deprives her of the winnings when her lottery number finally comes up. The family’s rented rooms shrink with their new poverty,, and Agathe, ironically, takes a job managing a lottery office. And finally Philippe robs the till at work, gets involved in a political mess, and goes to prison.

Agathe and Joseph enter a new chapter of their lives then: they travel to the provinces to try to save a pecarious legacy her brother should have saved for her from their father. Well, it is a struggle, and they fail. The last part of the novel weirdly veers away from Agathe and Joseph, while Philippe attempts to win the inheritance for himself. And lets’ just say, there is violence and the usual theft and ruining of live.

A Daughter of Eve is simple and slight, but I thoroughly enjoyed it. It starts out like a fairy tale. Two virtuous sisters grow up in total innocence and are shocked when it comes time to marry.

A Daughter of Eve is simple and slight, but I thoroughly enjoyed it. It starts out like a fairy tale. Two virtuous sisters grow up in total innocence and are shocked when it comes time to marry.

Here’s an excerpt:

Marie-Angelique and Marie Eugenie de Granville reached the period of their marriage—the first at eighteen, the second at twenty years of age—without ever leaving the domestic zone where the rigid maternal eye controlled them. Up to that time they had never been to a play; the churches of Paris were their theatre. Their education in their mother’s house had been as rigorous as it would have been in a convent. From infancy they had slept in a room adjoining that of the Comtesse de Granville, the door of which stood always open. The time not occupied by the care of their persons, their religious duties and the studies considered necessary for well-bred young ladies, was spent in needlework done for the poor, or in walks like those an Englishwoman allows herself on Sunday, saying, apparently, “Not so fast, or we shall seem to be amusing ourselves.”

Marie Eugenie marries a rich banker, Mr. Nucinigen, and Marie-Angelique marries a count. They thrive for a number of years–it’s better than living along– until one day, after years of virtuous marriage, Countess Marie de Vandenesse takes a lover, the journalist Raoul Nathan. And this becomes a problem, because soon everybody, especially Nathan, will need money.

Fun to read!

And now I say Adieux for the weekend, so I can catch up with my TV-watching!